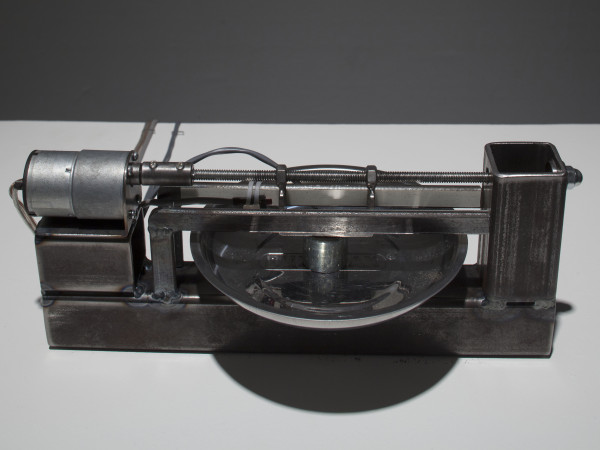

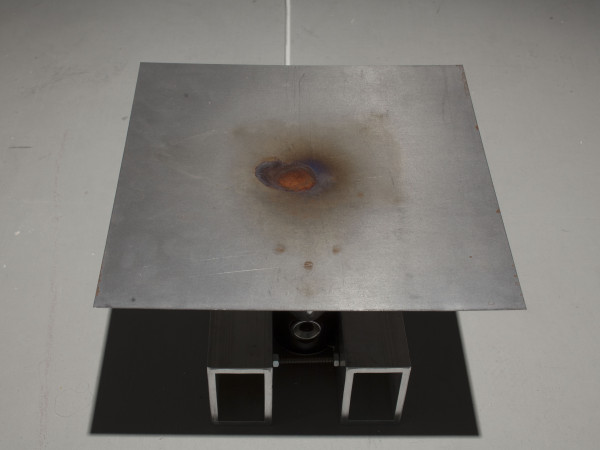

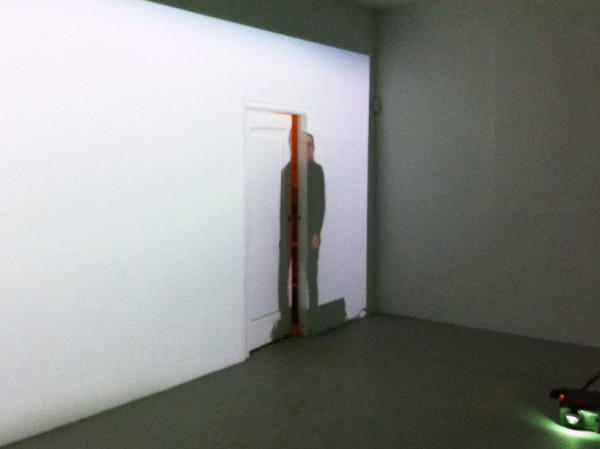

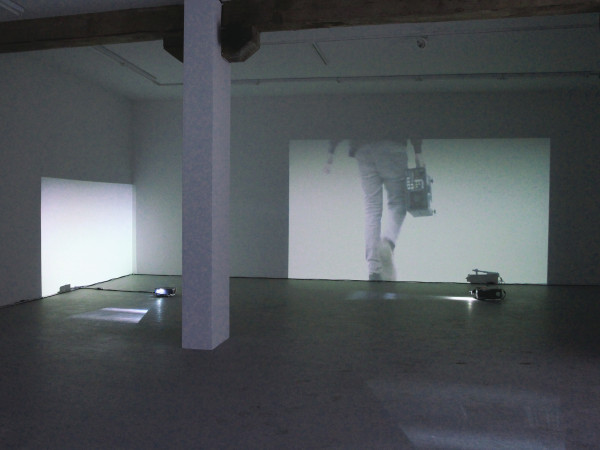

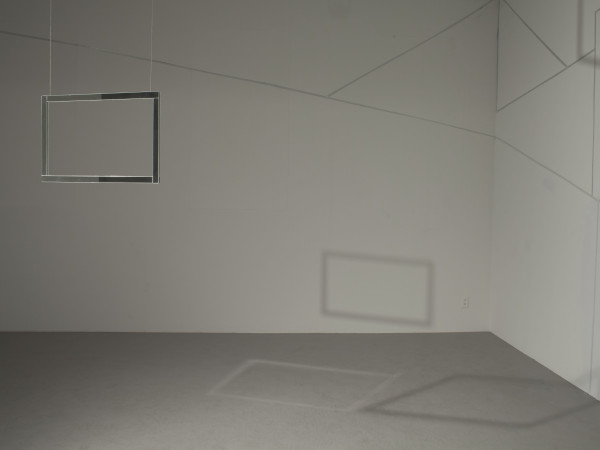

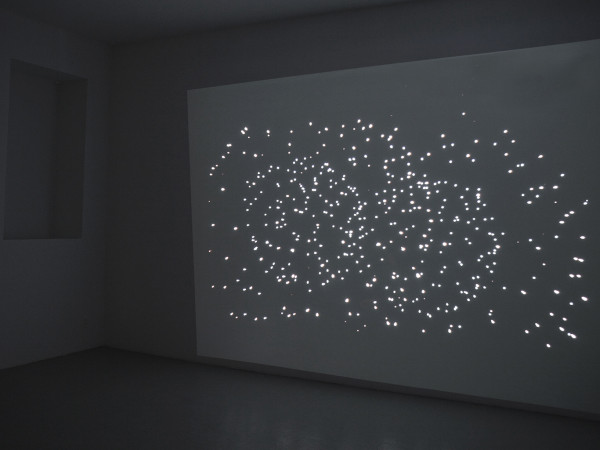

In the spring of 2012, LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE invited Marc Dulude to spend six weeks at a creative residency in Quebec City. In order to recreate his usual work environment, he converted the large gallery on rue Christophe-Colomb into an ephemeral studio: wood and rope structures, tables covered with diverse materials, temporary pedestals, machines and so on. In a laboratory typical of his artistic practice, objects create movement, are shaped and made into images, are transformed by natural phenomena like flowing liquid or oxidation, are manipulated by supporting structures that give them unexpected appearances or are captured as they explode, like the “water balloons” that burst day after day in front of a camera as an experimental process. For Marc Dulude, the art object seems the fruit of diligent research that is both technical and meaningful in which manipulation and thought are articulated.

Marc Dulude used his residency for experimentation. We took advantage of his time here to talk to him about this and other things, such as art and life, his views on creative production and the present-day reality of the artist. The following are extracts from a rich and fascinating interview that tell us much about making visual art today.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Is the way you’ve been working for the last few weeks your customary modus operandi…

… I look for a guideline, I find a thread and I also work in my parallel universe, on my computer. Usually, I don’t take my computer to the studio, unless I need it to make calculations. When I take it to the studio, at a certain point I stop working, it’s as if the computer takes over. And then, you no longer feel like working because working is also a physical activity, it’s a rhythm, if you loose this rhythm… then forget it.

I’ve noticed that art practices have tended to become modified because we’re all in front of a screen, and I think for some people the change in artistic practice is to give up the studio, to use it as a production space instead. The studio space now takes place within the screen, in a virtual sphere.

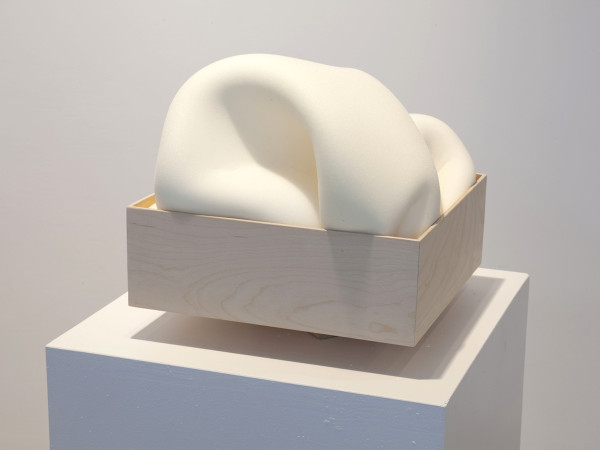

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Artistic practice, is it a craft, is it a profession?

It’s a vocation. It’s life. Someone told me: “you’re like a fish in the water here.” Like a fish in the water because for me I have the impression that there’s nothing new in what I’m doing here, in the sense of being in residence, working day-to-day, because it’s something I’ve done everyday for 15 years.

What do you mean by vocation?

A little like a religion.

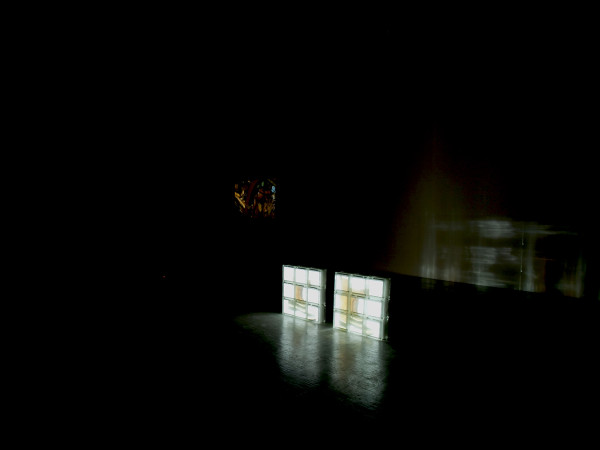

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

You don’t choose, some how? And you believe in it?

Oh, you know, we artists live a bipolar life. In fact, we aren’t bipolar but have a bipolar life. It’s fantastic good fortune or really slack times. The artists that are functioning best are probably those who have a head on their shoulders. We’re very down to earth and at the same time, we’re able to put things in perspective, in any case, those who succeed in functioning, in breaking through after so many years.

The practice is this: it’s something that you do everyday. This’s why it’s a vocation. You spend three days in the studio but you’re not paid for this. You do this because you believe in it, but you believe in what? You believe in: “OK, I’m going to the studio.” It’s not about winning a medal: it’s not sports! It’s narcissistic: it’s believing in an idea that YOU have.

Apart from the studio work, I imagine that you also carry out continual documentation work, in notebooks and so on?

Yes, I’m always walking around with my camera. In fact, the idea is to look for what you don’t see. I walk a lot in Montreal. When you always take the same route, the challenge is to look constantly where you’ve never looked before. It’s like a contemplative moment: in fact, it’s like seeking an awakening. I don’t know if you seek an awakening or if it comes to you… but I’m on the alert for it.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Do you think this is the specific work of an artist in society: to show things, make them stand out?

…showing what’s not seen, yes, I think so. It’s said that an artist should say something, whether there’s a social or political commitment. I think that the artist’s commitment can take another form, this form here. It’s like using binoculars in fact. We’re the ones who highlight in fluorescent to say: look, there’s something happening, did you know that you could do this and this?

Have you found an audience for what you do: are you satisfied with your work’s reception?

The issue of the audience… I don’t make a work to please someone, but I’m concerned with the other in what I do. I don’t try to make my art accessible to everyone, but the codes are there, if people make a little effort, they will be able to understand something, but in a world in which they are not accustomed! I think this is the magic of the visual arts.

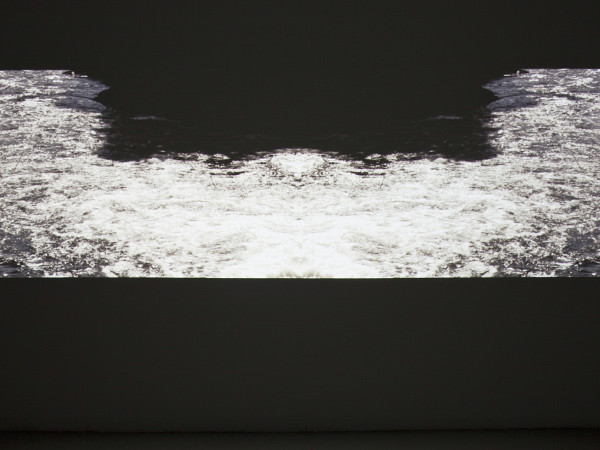

This makes me think of an anecdote. Visual art is a universal language: you can speak another language, come from another culture, and you’re going to understand. When I went to Niamey in Africa,1 I showed my sculpture with the moving water. The evening of the opening, there were four Tuareg people, ladies who appeared older than they were. I was standing beside my work and I was speaking, and it was clear that they knew that I had made the work. They came over to see me, pointing a finger at me saying: you made this? They were speaking to me in a language that I didn’t understand and the four of them began dancing around me… I said to myself, OK, here I’ve done something that has surpassed the boundaries of my own space. As my teacher in the master’s program told me: you know that your work functions when another culture tells you “I understand what you’re doing.” It’s abstract, this…! It isn’t a landscape! It’s a table, it’s water that vibrates… there’s all this imagination here that’s going on in the head!

I’ve always liked playing with the boundaries of abstraction, of being able to look for this limit in which I don’t represent the object: what does this do? I prefer to play with peoples’ imaginations. But today, this can take forms other than a patch of colour, or abstraction, I think that it’s here, I say it and I think it, it’s something that has not yet been really explored: this type of relationship, the association between the object and the mental image…

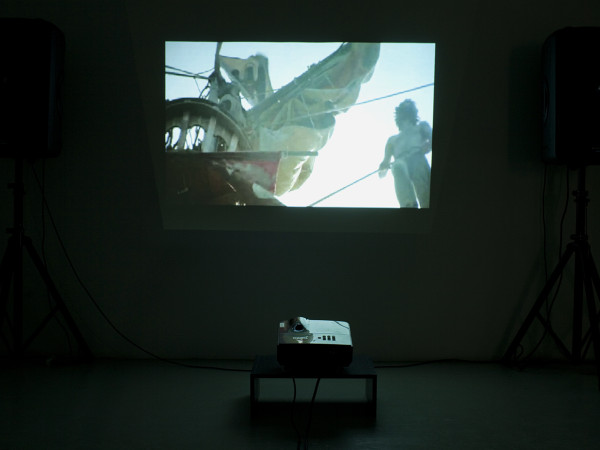

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

It’s true, I think it’s something in particular that one could explore, perhaps it’s even research specific to our time, in art, because we’ve broken down the boundaries of figuration and of pure abstraction.

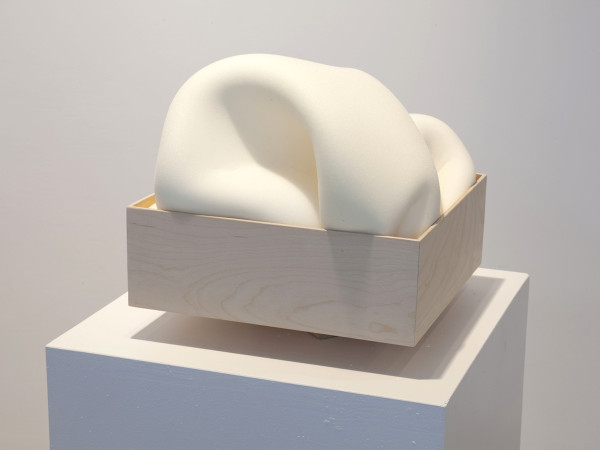

Yes. What do you do to be able to… not go against it, but to play with this kind of association here? In your head, when you do whatever, what is it that makes it a piece that works or doesn’t work? This is the boundary. Right now, I’m working on sheets of paper on the floor. Honestly, in my head it doesn’t work, it doesn’t click: it’s not there yet. It’s things like this. Do you see that white piece there, it’s a gesture that I made quickly and for me, there’s something there…

…yes, there’s something there, I agree, it caught my attention right away, I feel like touching it! There’s a potential connection that takes place, in any case…

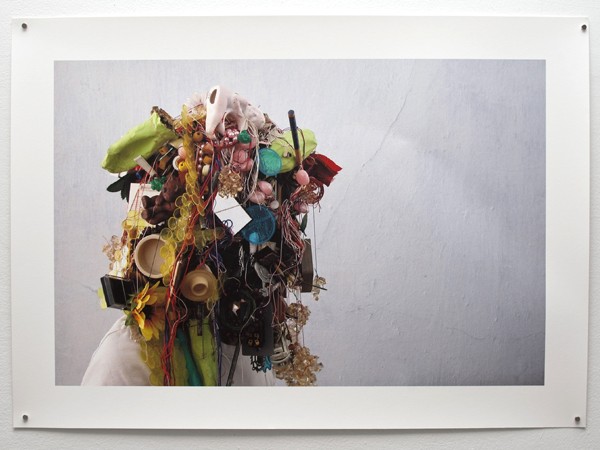

For you, you’re making sculpture?

I’m making objects. Objects because the object can be an installation as well. I consider that photography is also an object: it’s a photograph! In fact, it’s all new what I call this, because I find it’s shorter than to say I make sculpture, installations, photographs and sometimes video. I find that saying I’m making objects covers all this. In fact, it names what I do a bit more than just saying I make sculpture.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

You could say that there are some who make objects, others who make images and still others who carry out actions.

That’s right, but I don’t work with images, I’m not a specialist in images.

You work with volume and mass.

That’s right, even when I do photography, even in this case here.

It’s still a matter of volume…

Yes, it’s still the object. I work with the idea of recycling. I recycle the object: I take it and play with it. I even go to places where artists generally don’t go, which is to the craft.

And you accept this completely in your work as an artist, the matter of know-how?

The matter of know-how is significant because it’s part of learning about the object. When I talk about the material, it’s a way of understanding physically what it is, what’s there.

I find that your work is closely related to this. It’s the property of the material itself that is taken in another direction or diverted by a small intervention. Looking at your Website, I thought to myself, it’s really these properties that are exploited in your work. And in looking for the significance…

Yes, yes, the significance is there, in fact it’s a matter of heightening it, it’s always this that I like, it’s the poetic gesture in the object: “Ah! There’s something beautiful in it.”

Yesterday, when I presented my Website, there were people who told me: “it’s fascinating Marc, you go in all directions, the core is there but it’s fragmented.”

Do you have this impression about your work?

No, it’s this… In all directions, probably is more in the way I deal with things, but the heart of the work is always there. For me, the lineage… there are many artists whose style we’ll recognize in ten years, recognize that it’s their work. With my work, this won’t necessarily be the case. I find this interesting: life, it’s never the same story!

- Marc Dulude represented Quebec at the Jeux de la Francophonie Games in 2005 and won the silver medal for sculpture. The installation was presented at Verticale in 2007 and at Circa in 2008, having the title Œuvre sur toile.