Entering into the gallery, in the middle of the space, the viewer is overcome by a strange sensation of vertigo: a loss of balance and control. But the vertigo does not come from height: instead, the impression is that the body is thwarted, notions of space and time shattering the visitor’s habitual world. This is because in the work Box de sombra, everything is to be redefined. Even the gallery space, so familiar, does not manage to give the minimum of stability. Free from its function as an exhibition space, it becomes for a moment or infinity, the work itself.

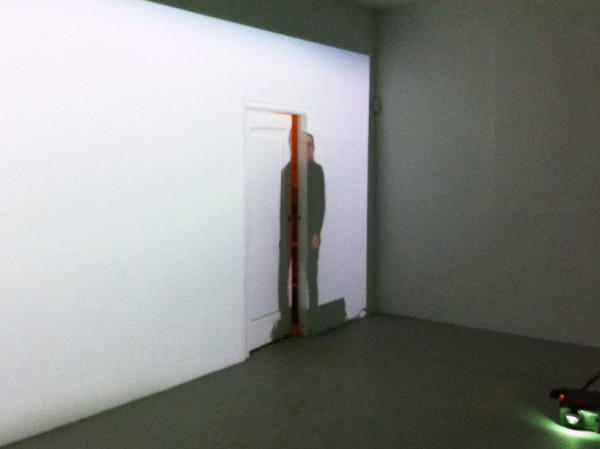

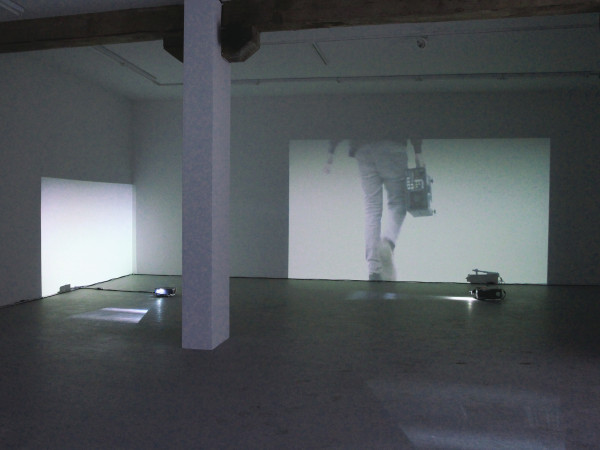

To create Box de sombra, the Mexican artist Miguel Monroy placed four projectors on the ground. On each of the walls, he projected the image of this same wall, on which one can see the artist and LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE staff move about in an endless kind of round. Each one in turn enters the exhibition space, as if we were at the stage of mounting the work. The image of their body is lost for a few seconds, the time it takes to cross the gallery for instance, and then it reappears on a wall, in order to install one of the projectors. While the viewer’s gaze is still fixed on the moving image, attempting to grasp the duplication of the space, another member of the staff makes his or her entry. Then another and thus it continues. Caught in the middle of this choreography, where the visitor seems to be the only one not knowing where to stand, wanting to catch the eye of those who continue to come and go. Because even if this person is completely aware that it is only a play of projections, he or she cannot help but be constantly troubled by this place in which fiction and reality intersect. The markers are constantly shifting, leaving one in doubt about the boundaries of the work.

In a complex process of mise en abyme, usually described as the work within the work, Monroy leads the viewer to question the structure of his work. The history of art has many celebrated works that use this procedure, such as Jan Van Eyck’s Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his Wife (1434) in which a mirror is place in the background, allowing us to see the painter at work. This view of the work––that prompts “a return to the signifier,”1 according to the terms Christine Dubois uses in her study of mise en abyme–is recognized for its introspective power, causing the viewer to become aware and question the making of the work itself.

But what is the actualization of this process? Following the preoccupations of contemporary art today, it seems that mise en abyme tends to be concerned with the implications of exhibiting works and the viewer’s immersive experience.

On this subject, it is interesting to make a parallel between Box de sombra and Thomas Struth’s Museum Photographs in which the latter shows photographs of viewers looking at paintings.2 In front of these works that repeat the action of the moment, the visitor is directly concerned, almost forced to question his or her behaviour and situation in the exhibition space. If the same kind of reflection is produced in Box de sombra, it is however, with a somewhat different intensity because the viewer is directly part of the action. Like it or not, the viewer is at the centre of Monroy’s work. What is more, one could say that he or she is literally in the spotlight. The beams of light from the projectors create a shadow of his or her body and show it on the wall, propelling it into this space where two distinct realities interlock. While becoming familiar with the work, visitors can play with their shadows, changing the scale as they move around in the gallery, accessing the more playful aspect of the work, which is a recurring feature in this artist’s practice.

Having a strong multidisciplinary approach, Monroy initially worked with the idea of the ready-made, diverting the meaning of everyday objects and changing the conditions of their presentation. In his works, the artist at times pushes the play until it reaches the level of the absurd, such as Walking Machine (2008) in which he experimented with the possibility of riding a scooter on a moving walkway. Box de sombra is situated in continuity with this practice, even though the artist is exploring new territory and new dimensions, no longer questioning the meaning of objects but rather that of the gallery. Inspired by the residency project at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, which offered him the chance to work in the gallery for several months, Monroy decided to broaden the in situ experience, concentrating on the specificities of the artist-run centre placed at his disposal, that is to say, its equipment, space and staff. In fact, the great strength of his mise en abyme is found in this closeness of the work to real elements, creating an actual blurring between the exhibition space and the work, just like between the time of its installation and that of its presentation.

But beyond the confusion that surrounds the parameters of place and time, the vertigo felt in front of Box de sombra is constructed through the repetition of actions, making the work reel toward the exhilaration of infinity. In fact, the rhythm of the projection loop produces the impression of suspended time, as if the work is never finished being installed. However, as Monroy’s sensitivity suggests to us, this kind of system often has imperfections. The artist made a brilliant demonstration when he changed some pesos into dollars then did the operation in reverse, again and again. Following the principle of equivalence of worth, the transactions should have continued indefinitely but very soon, nothing was left. What about Box de sombra then? The repetition of this same gesture––that of installing the work––does this not reveal the actual nature of the exhibited work? If the mise en abyme makes us see the genesis of the work, it also reminds us that this in situ work, woven into the actual place where it is exhibited, cannot be distances forever from the moment when it will be dismantled. There seems to be something predetermined for this work, but also, perhaps, for viewers that wander among the four walls of the gallery.

Box de sombra. Boxe de l’ombre3. Shadowboxing. Like boxers who train alone, imagining the reaction of their opponent with their own shadow, the visitor to Monroy’s work is confronted with a kind of void. Despite all the people, the shadows and projections that come and go, solitude seems to reign in the bare gallery space. In questioning this place of encounter between visitors and works, is Monroy making reference to a battle in which the outcome is already determined?

- Dubois, Christine. 2006, «L’image «abymée»». in Images Re-vues, No. 2, Document 8, p. 2. Website [online]: http://imagesrevues.revues.org/304 (consulted on November 28, 2012).

- Schmickl, Silke. 2005, Les Museum Photographs de Thomas Struth: Une mise en abyme. Paris: Maison des sicences de l’homme editions, 2005. 77 p.

- The expression “boxe de l’ombre” is a reference to shadowboxing, a training exercise used in combat sports.