Coming soon

Coming soon

LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE always proposes site-specific residencies based on the relationship between the artwork and the premises. From 2014 à 2016, faithful to this mode, four projects explored, furthermore, the sometimes troubled relationship of the individual with its environment.

In the fall of 2014, Nancy Samara Guzmán Fernández and Rodrigo Frías Becerra sneaked into the bureaucratic universe of the government employees scattered every day on the 31 floors of the Marie-Guyart office tower. The Mexican artists, weaving through the screens forming the work cubicles, brushing lightly some green plants that were expected to animate the decor frozen under artificial lighting. These plants, Not Wild, But Still Life, who could be seen in the windows, gave off a friendly impression of the building, but in reality, everything was ordered to keep workers in an environment foremost functional.

In 2015, the Transcultures exchange program Vice Versa wove a network of residencies between the Web, Quebec, and Mons. In that context, artists Alice Jarry (Montreal) and Vincent Evrard (Liege) were paired to conceive and build an installation inspired by diffraction that explored and “brought into light” this phenomenon with the help of glass, mechanisms, and electronic devices. According to the co-creators, Lighthouses is at once plastic, poetic and metaphorical, because the work reflects the process by which the light is deflected or diffused in beams of different colours when it encounters an obstacle: this process mirrors their work methodology, their material and what occurred in their collaboration and the premise of creation.

In 2015, also, the Canadian-Mexican Michelle Teran furthers her research on disturbances in the urban environment (previous residency in 2006). This time, moved by the issue of social housing and urban diversity, she explored downtown Quebec City. Five social organizations concerned with the same questions opened their doors to her. She shot videos documenting their activities, their mission and specific cases. These videos fed the discussion around the issues to which this “art sociologist” wants to raise public awareness.

Finally, in the spring of 2016 the Thai artist Jedsada Tangtrakulwong had to adjust to our persistent winter. Through his wanderings in the cold of the environment, he was fascinated to see how the City had designed a way to swaddle the trees to protect them. His installation, Adjust, reproduced in the gallery this manner to be creative in order to survive. Everything becomes a matter of adjustment, in art as in horticulture.

Is it the case that people, places and things are only what we think of them? How can we put ourselves in the shoes of the Other? The artist Luis Armando García is interested in the role that tourism and criminality – as reductive as they are antithetical – have played in shaping the image of Mexico. In Viento del Norte, he sought to present another reality of his native country – far from stereotypes – that of ecology. However, it is not easy to abstract the violence that bears down so heavily on everyday life in the country. This violence poisons the climate, and is carried by the winds of the North. And so it was that, irrepressibly, dramatically, Viento del Norte changed shaped over time, and became Linea de Fuego.

García’s extended residency at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE enabled him to explore his social, professional and personal identity from a range of viewpoints. It enabled him to understand, in new ways, the places from which people speak, and to reflect on the subjects of which people speak, and how they do so. As an interrogation on the nature of identity, appearances and communication, the substantial body of work that the artist produced during his stay expressed perfectly the fact that places, things and people are, to a significant extent, what we think of them, and what we make of them.

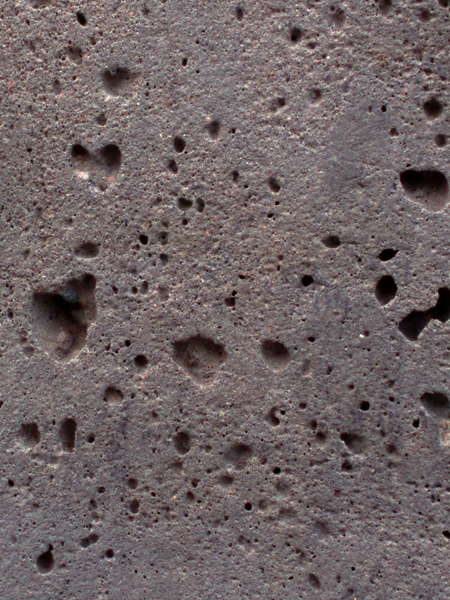

Viento del Norte was both a poetic and meditative installation that centered on the correspondence between the rigorous desert climate of the Zacatecas and that of the Quebec winter. Drought, as much as intense cold, influence social behavior and mood. Despite environmental differences, and differences in modes of adaptation linked to geography, in both cases tension plays a role in creating a form of anticipation and a particular means of naming meteorological phenomena such as rain and snow. A metaphor takes shape around this observation: that of the possibility to feel empathy for the Other based on one’s own experiences. This metaphor was translated with both sensitivity and efficiency in Viento del Norte by means of juxtaposing contrasts, albeit involving similar forms. Many visitors were amazed at how a Mexican, from a desert region, with no knowledge of snow, so clearly expressed the reality of the North, and furthermore with objects inspired by, or modeled after, forms used in arid areas to gather rainwater.

Such was García’s exploration. Beyond forms of prejudice that categorize people and destroy communication by affirming the differences between people and things, García seeks out that which is common. He identifies similarities, and based on these he extrapolates and constructs bridges that cross the divide between appearances and differences. This is no simple strategy, and it is one that has a precise effect. It endorses the artist’s discourse on the circulation and perception of identities, given that these are the very objects that he takes and re-stages in his creative process. The porous rocks that are used to filter and purify the all-too-rare water in the desert have featured in a previous group exhibition in 2002 in the town of Zacatecas. Once relocated to Quebec, they are replicated and molded, literally, on the local context. These water receptacles, chalk-white in color, cone-like in shape, whether in liquid or solid form, perfectly evoked both heat-waves and waves of cold. And so, that which travels, he who travels, is transformed, penetrating the universe of the Other, by means of his own experience. Given that we know both the heat and the cold, we can imagine the torrid and the polar. However, for those who have difficulty with one or the other, it becomes arduous to imagine living in such states on a daily basis. And for those who have never experienced frost, it is difficult to imagine that it can cause burns just as painful as those produced by fire.

The same can be said of violence. For those who have no real experience of such things, it is difficult to imagine the effect that it has on people. Imagining violence as a part of daily life is horrible for anyone who has experienced, even once, any kind of traumatic event. When the reality of the Other is too distant from one’s own, so there are obstacles to empathy, to the process of “approximation”, which gives way instead to indifference or contempt.

As a Mexican citizen, representing his country, Luis Armando García is situated at the point of convergence between attitudes that he indicates he often encounters amongst strangers. These fluctuate between a conventional exoticism, the denial of responsibility (faced with the humanitarian catastrophe and distress of the Other) and moral judgement. He finds that younger people are often more open to, and moved by, the political content of his work, perhaps because they are in a process of self-discovery, they are more open to the reality of others. The artist’s experience of the gaze and the perception of viewers is noticeable, and his concern regarding the judgement of the Other often surfaces. He mentioned on numerous occasions his pleasure at walking the streets of Quebec City, without the fear of being attacked, and without the burden of the perpetual tension that is, he explains, palpable throughout Mexico. When fellow Mexican performers arrived in the town and asked whether he had any recommendations of places to go, he suggested that they, “walk around the city and savor this unusual feeling of ease.” He insists that Mexicans are no more violent than the Quebecois. Rather, violence has taken hold insidiously over the years in the country, in connection with crime, and often linked with corruption. What can be done, faced with the spread of criminality, which now operates openly, including in his home town? Barricading oneself in, becoming a prisoner of one’s own fear, is hardly a solution. In succumbing too much to the mindset of protection, there is a loss of belief in the possibility of change. And so taking a position and acting has become a necessity for García, and this is a choice that he makes both in his personal and professional life.

This is why the white and fresh energy of Viento del Norte gave way to the heavy and threatening atmosphere of Linea de Fuego. Whilst the concept of the first installation was clear to the artist prior to coming to Quebec, the second installation, whilst present, lay more dormant as a concept within him. Linea de Fuego was grounded in the deterioration of the situation currently in Mexico and the grief of the recent death of a friend, a victim of assassination. Following the first few weeks of his residency, and the completion of Viento del Norte, García was faced with the proposition of unsettling things and stating, clearly and with urgency, that reality is something other than what lays before us; that life is more than appearances, and that just as poetry can be violent so violence can give rise to poetry. Moreover, poetry can be laden with tension.

The second work staged by Garcia dealt less with violence than its consequences, those of feeling trapped and powerless faced with the unknown. A number of elements, as coherent as they were troubling given their unfamiliarity, coalesced to create a no man’s land, where it seemed that anything could happen, for better or for worse. A sinister bunch of chains stood out immediately on entering the space. These were suspended from the ceiling and anchored to the floor, a hanging form that moved almost imperceptibly with the action of a motor. Visible through these iron tentacles, a web of electrical wires clung to the wall, with small bulbs hanging from their ends, like the synapses of the nervous system. Projectiles hung in front of them, in mid-air, like lead lines, sounding out obscure regions of the human. A lugubrious noise brought shudders: water in a pool bubbled as, on the surface, archival footage depicted the words of a hostage, who was soon to be assasinated. It is clear, without explaining each element, what the overall effect of the works suggested and demonstrated.

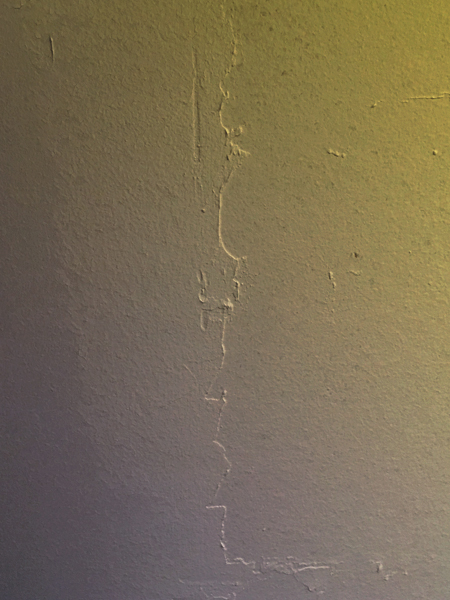

Beyond this, a noticeable feature of the work, for those who had witnessed Viento del Norte, was Garcia’s reuse of all the elements of the previous work. In a manner of speaking, the artist had dislocated, dismembered, kidnapped so to speak, the constituent parts, the witnesses of his first work, torturing and disposing of them in a completely different fashion to say something entirely new. A number of works, presented as paintings, bore the traces of their previous incarnation: plaster marks, rust stains that, along with the spectacular cone-like forms that now dripped rust-colored water along their once-immaculate form, spoke of bloodstains.

On a final note, it was astonishing to observe that fragments of fractured concrete paving stones in the space were hanging by a bare thread, which seemed mockingly, to symbolize the fight against the chaos all around. Yet, one must intervene, act and gather together the pieces of that which is broken. Such a gesture is not naive. It does not pretend to repair. It is a form of testimony. It is a matter of taking position and, faced with the undeniable difference of the Other, not succumbing to cynical fascination, to comfortable indifference, or to moral condemnation. This is important, because in the end people are to a significant extent what we think and what we make of them.

In 2008-2009, themes seem to resound from one residency to the other although in very different spheres such as: music, displacement, traces and colours. Erick d’Orion first takes us in the confusing course of his Forêt d’Ifs, a sound and visual “hyperfluxienne” experience. The deafening location, visually frightening, falls more under the scope of a nightmare than reverie.

It is instead Mamoru Okuno’s sensitivity and refinement of gesture of that bends our ear to the simple music of our daily lives. Through relational rituals, the artist manipulates banal objects of everyday life on which he draws our attention to let us hear their language.

Both meditative and open to the location, both physical and metaphysical, James Geurts’ artwork is crisscrossed by the fluidity and the transience of its devices and forms, as so many narratives about travelling, water and human encounters generated by the art space.

The Unfinished Tour Québec City again addresses the question of displacement, but of a different nature. Here, it is Gabriela Vainsencher’s displacement in relation with the art of the Other and the residency environment, but also the displacement of points of view brought on by her drawings that can be considered as ‘’illusionist projections’’ or as the traces of her experience left on the outside world. Other traces are offered by Antonello Curcio’s À hauteur du regard. His installation celebrates the materiality modulations of white . An algorithm unfolds on the walls, comprising the entire space of the gallery : sometimes three-dimensional, sometimes two-dimensional, his monochromatic squares follow one another as the result of meticulous interventions of scraping, incisions, pigment and graphite applications.

Through the energetic impulse of red, it is still the question of the colour vibration that is addressed in Robbin Deyo’s Flow. Red lines on a white backdrop follow one another, inhaling and exhaling on the walls, to the point of hallucination.

Michel Certeau’s concept of the “the practice of space” find its relevance in LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE’s 2007-2008 season. It is indeed question of constructive moves and perceptual reversals, in a space that was successively broken, ritualized, fleeing, naturalized and updated during the five residencies that followed one another, each requiring a different posture on the part of the viewers who “practice” the space through the artworks.

Fnoune Taha throws a philosophical light on Virginia Medeiros’ approach. The Brazilian artist’s artwork À contre-sens covers the transgression of gender and social class. Videos shot in an underprivileged area of Salvador, show the diverted paths of two marginal, Simone and Preta.

Jean-Pierre Guay chronicles Gabriela Garcia-Luna’s last voyage, Universos relativos, true rite of passage in three steps by which the Mexican artist approaches the death of his father. It is a matter of suspending time to reach somewhere else by crossing the present reality.

With Possible Worlds, a sort of construction site, artist Erik Olofsen seeks to deconstruct our perception of space. Annie Hudon Laroche underlines how the artist realizes constantly ‘fleeting’ spaces, between fiction and reality, through ‘’ mises en abyme’’, duplication and juxtapositions.

In Ivana Adaime Makac’s Le banquet, plant sculptures under glass domes are animated by the chirping of crickets: six enclosed spaces doubling back on the slow pace of small worlds, combining life and death, summoning, “the delicious or the abject’’. In his text, Denis Lessard recalls the relation between insects and creation.

Sébastien Hudon covers Exils intérieurs from Belgium artist Els Vanden Meersch. In the exhibition room in a sort of black bunker, photographs of empty interiors both strange and familiar, instill an unstoppable anguish: their icy austerity evokes the barren rigidity of totalitarianism.

Although Alexandre David detests disciplinary categorizations, he considers himself a maker of sculpture. Whilst he works in a number of diverse practices, which he regards as secondary, his preference is for sculptural installation. David’s objects are also spaces; his work deals with our understanding of space and objects, and the complementary relationships that exist between them.

Over a period of five weeks, David transformed LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE’s exhibition space into a joinery workshop; wood is a very enjoyable material to handle, the artist tells us, and is something that can be recuperated. The doors opening out onto the street carried with them a fine dust and the perfumes of the forest.

The first week of David’s residency involved the hanging of threads in the space, forming a three-dimensional sketch. The artist is a perfectionist, which led him to rework his idea over twenty times during the process. For example, in order to avoid juxtaposing an impeccable cut of wood with the irregular, and potentially disruptive line, of the ceiling he decided to leave a slight space between the two. Initially, the final form of the work was to have been an L-shape, allowing movement around the work. This plan was abandoned. Boxes built at ceiling level were also demolished halfway through, after a week of consideration:

“I took them down. I had the impression that I was simply reproducing a traditional cloistered form, with a roof and an empty center. It was too loaded. It interrupted the tone of the work, turning the space into a single entity, when I wanted to create a number of very different spaces. If I had another six weeks, I’d do it, build and fill the space with them. Just to see. But it’s always a question of choices.”

“When I arrived at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE I saw two systems: one, parallel to the street, consists of two walls with columns in the center; the other is autonomous, and independent of the street. So I wanted to explore these two directionalities in the space: to emphasize the columns and the experience of separation, and the distinction between two halves.”

Alexandre David’s installation demanded an effort on the part of the viewer for it to be properly appreciated. This was not because the work was hermetic in nature – the artist stresses that his work is not intended to be conceptual – rather it is experiential. In order to grasp the intentionality behind the work, one must therefore scale it. Here I attempt to retrace the journey that he proposed, with the help of the artist’s words.

“Being up high on the work gives us a sense of direction, because when we see its surface, we see that there is no access into the space at any point. We can come back down or go higher. If we go higher, something happens: we realize that there is a curve near the base of the work that is barely noticeable. It is not a visual curve, but a curve in the base of the structure that we feel when we are walking on it. Why is the curve there? I wanted to create an architectural environment, not in terms of design, or creating an interior in which my installation would become a type of loft. I was more interested in exploring the relationships between different types of sensation to create something singular, something new.”

“The sensations that I am referring to – such as walking on the ground or climbing a slope – are sensations that are associated with exterior architectures. When we climb a hill there comes a point at which we slow down: the angle of the slope becomes less steep, as it levels out at the top before descending. So we stop, turn around and look at the other side. My curve recreates the exterior sensation that prompts people to turn around and look at the other side of space. This is a good example of how I work. I use ordinary things from everyday life to create events.”

“We also feel that the slope is rounded in two directions, which pushes us to the corners, always in a kind of slowed down motion. I didn’t want the work to be aggressive; I didn’t want people to climb straight up the structure and run into the box forms. Instead, viewers can come and sit on the structure, under the boxes, as in a cave or when sheltering under trees or a roof. A range of architectural sensations are in the mix. It’s as though we are protecting ourselves from the sun, from bad weather, this is how the elements of exterior architecture work in my installation. At the same time, the way that the walls are layered with plywood and forms overlap in space, each one positioned in relation to the previous, evokes the feeling of an interior architecture.”

“In addition to these sensations, I play on the familiarity of architectural features such as the height of a step or a bench. For example, the point at which one climbs up on the installation, the step, is much higher than normal. But on the other side, nearer the wall, the step looks more like something found in a park, perhaps a bench. The space marked out by this step (or bench) forms a corridor. The environment is therefore composed of elements that are reminiscent of known architectural features, except that my intention is not to evoke a structure that is already familiar. Rather, this approach allows me to propose something that – given its uniqueness spatially – is not really architecture at all.”

“Ultimately, the particularity of my approach lies in the way that I create objects that, quietly, become spaces in their own right. This transition takes place slowly, and from two directions. Beneath us, the platform does not make contact with the wall, it acts and functions as an object. The structure then continues forward, joining back up with the wall, meeting the wall in a way that transforms the object into a site. This accentuates the feeling of turning a corner, prompting us to turn a corner: the title of my residency refers to this sensation.”

“My work has no symbolic value, it says nothing about the world. We discover nothing in it other than what we experience. On the contrary, such symbolism lies on the other side of the work, it forms the foundations from which we are able to experience space. Once the experience has taken place, it has no further significance for me. It can however be related to the everyday, to our knowledge of architecture, prompting us to reflect on space, and perhaps to acquire a critical perspective, as is the case with all art that reconnects us with life. But there nothing to decode in the work.”

“One could, stretching it, speak of a formal experience, but I don’t really like this term, because it often refers to experiences that are separate from everyday reality. I’d speak of perceptual, sensorial or event-based experience, but certainly not of intellectual experience, even if I am able to intellectualize it after the event.”

“One last thing is important, the installation is not a solely visual experience. It involves a meeting between the visual realm and use value. The work does not involve simply looking, or conversely simply sitting. It involves a meeting of the two. One must no longer be able to separate the two, except in terms of language. The work is not merely a functional object. We have to use the space that we see, and for that we have to draw on our basic knowledge of architecture: for example, our everyday experience, when we are young, of hoisting ourselves onto chairs, or of climbing a ladder. Of course, there are more visual moments, images, in the work. Climbing up at this point creates a frontal, visual experience that is supplanted by the sensation of the curve in the floor. I modified a slope during the making of the structure, precisely so that it was not too visually apparent.”

Personally, I am more intrigued by the formal nature of David’s work. My body no longer senses the subtle variations that the artist has introduced into the work, based on his extremely rigorous handling of materials and calculations. I am more attracted to the logical impossibility, the improbable and nevertheless visible fusion of two uneven surfaces juxtaposed with the ground. I am more attracted to the fact that the slope leads nowhere. At the same time, I am tempted by the corridor in the work, which offers a means of moving around amongst other viewers that seems more convivial.

David specifies that he, “wanted to create a form of symmetry, of equivalence between the two spaces. At the base of the structure there is a hollow in which people can walk, and up top there is a hollow in which people can sit. If you stand up, you hit your head, or else you have to walk hunched over. The spaces are, therefore, static (points at which to observe an empty center) as opposed to spaces for walking around (in which you can observe something as it transforms into an image). The voids are a form of punctuation in the object. At the top and the bottom of the slope there is an inversion of volumes. I like this notion of inversion, of negative volume.”

On entering his installation at la chambre blanche, Alexandre David saw a form of public space, an empty center (a city center perhaps?) surrounded by walls and encircled with boxes. The project is an extension of an approach that he has been developing in his practice as a whole, whereby the object becomes a site. He is increasingly interested in architecture and less and less in the creation of defined objects. His next project/space, planned for Montreal, will consist of a mobile public space on wheels, with plastic cases that can be opened.

David has always been interested in the architecture of public space, without knowing why. Gradually, he began to perceive public spaces as a form of knot, a focal point from which collective decisions are made. Collective, public space is extremely important to the artist; the physical and material agora inflects the ways in which we work together, and construct community. Architecture, he says, plays a part in a holistic vision of the world. It draws together all aspects of life. It’s a question of ethics, of generosity in the world, of going beyond individualism by creating or collaborating on the creation of forms of critical reflection on collective space. This seems to be shrinking, according to the artist, “We are sold collective space on spectacular terms. Here is a new train station, a new airport, a new museum…”

David prefers working in something different, something unique: “My work is ephemeral because I have no desire for my projects to be installed permanently in space.” The artist wishes to work on small-scale projects that reflect on architecture that influence experience and contribute to the sharing of ideas and the senses. Therefore, although he claims that his work is neither political nor symbolic, he is conscious that it is situated in political space.

He concludes that, “art making draws us into the collective sphere because it involves addressing the other. This is even more the case when the work takes place in public space, at a site that interests the public.” In sum, David wishes to prompt us to reflect on this subject, which does not exclude the rural experience, whilst his preference is for urban settings.