Coming soon

Category Archives: article

Esther Roca Vila and the spontaneous gesture

Coming soon

Giulia Vismara: Sound Designer

Coming soon

Bangkok/Quebec Exchange

LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE inaugurated in very beautiful fashion the progressive opening of the international exchange Bangkok-Quebec. On a sunny winter Saturday on March 19, 2016 a wandering was kicked off with Jedsada Tangtrakulwong exhibition Adjust, which proved to be one of the highlights of the day, if not of the event.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

To Adjust as an Attitude of Creation

To survive or perish in the cold of the winter? Such was assuredly the question at the basis of Jedsada Tangtrakulwong’s creativity (his work). Used like so many of his countryfolk to a climate bordering on 37 degrees above zero, what happens to humans, wildlife, flora and water during the northern winter when temperatures can reach 37 degrees below zero? Although he knows that such climates under other skies have created civilizations and environments that developed and adapted to the cold and snow, how would he live this experience in coming to Quebec City?

It can be said he will have had only one attitude in mind: to adjust himself. From a human posture he will bring on an attitude of art. It was during his initial contact, his walk in the neighborhood, that a single observation will have triggered his skills. The ever-smiling Tangtrakulwong experiences in an extraordinary manner, something that, to our urban wintery eyes, has probably become so familiar that we don’t pay it any mind, something that will be a formidable trigger for his work. I am talking about these small trees planted by the City and that the municipal employees “dress up” with blankets and support with tutors for the cold season. As we will see, Tangtrakulwong will apply several artistic variations of this procedure, but inside!

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Sculpting the coatings

Looking at it as a whole, Jedsada Tangtrakulwong’s Adjust seems to have transformed the space of LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE in a luminous way.

The floor shines to better enhance the sculptural occupation on the premises. As so many islets, forms which will later prove to be shelters are scattered on the ground.

As we walk among them and get closer, our perception turns into singular discoveries from one work to another. These carved structures of variable sizes are wrapped up as so many domestic plants with a choice of coatings made from various materials with insulating properties. These coatings presented by the Thai artist appear as an undulating and fascinating architecture. Taking advantage of advanced technology combining computers and cutting tools program, the artist is inspired by shadows obtained by the lighting of potted plants to create the visible forms.

Each work is a discovery in itself. Sometimes, we must bend over to see the plant, or even to lift up a lid. Two shrubs, the biggest, stand out. Their branches are covered with felt blankets just like those the artist had found outside.

The adjustment as a survival mode here operates through inversion: from the outside to the inside, for the small outside trees, as a transplant, but also as a change in the function of the pot to that of a wrap protecting metaphorically from the cold, as we do with our coats and our homes.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Hearty exotic

Already remarkable for its layout, a warm exotic expressiveness emanates from Adjust devices. Having participated to the Thai side of the exchange1, I found myself daydreaming of the complex and fluid architecture of the numerous Thai temples that structure the cities and villages. For instance, it is the case of the famous Wat Arun in Bangkok.

But already, the visitors were beginning to move around. I donned my coat, hat and mittens carrying in my mind the shelters for plants invented by Jedsada Tangtrakulwong. Walking in the snow and feeling the sting of the cold on my face, I understood that the extension of the idea of protection embraces all that is alive. This leitmotif would probably cross the exhibitions produced by other Thai artists in the Medusa cooperative building, at Le Lieu, centre en art actuel2.

“Mixité” from Michelle Teran, or the efficiency of the documentary approach

The residency of the Canadian-Mexican artist Michelle Tera at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE in the fall of 2015, took place under the sign of “Diversity”, an issue that closely affects the central areas of Quebec City. Michelle Teran’s brings on a reflection about the meaning of the word that is too easily diverted by our politicians when it comes to intervene in the development of these areas. A video camera in hand, Teran has interviewed five social organizations concerned with the issue of housing in Quebec City and followed some of their activities to produce many short documentaries, presented in the gallery in December. She interviewed the FRAPRU (Front of popular action in urban redevelopment), Le Bail (office of animation and information on housing), Mères et Monde of the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Committee and the PECH-Sherpa (program of clinical mentoring and housing). In addition, two videos focused on important moments of social demands in the fall of 2015: the ‘’Night of the Homeless“, on October 16, in the area of Saint-Roch (Quebec University Square), the ‘’Social Strike”, with the occupation of the office Sébastien Proulx, MP for Jean-Talon district, and the occupation of the National Bank headquarters on René-Lévesque Boulevard by community groups on November 2 and 3. All these films were presented in the gallery of LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE in parallel on seven flat screens—five small-sized aligned on the same wall, and two medium-sized set separately—supported by a full-wall projection showing the poster of ‘’Communautaire en grève“ (Community on strike) installed on the façade of an abandoned building on Saint-Jean street.

In keeping with her previous work, Michelle Teran sought by this installation to resound at a deeper and more universal level events filmed in order to reach an audience that is not necessarily aware of the concrete work of these social organizations, or of the daily lives of the people who are involved. The parallelism between the videos running simultaneously on multiple screens and in the exhibition space emphasized several points of convergence. Although the organizations chosen by Teran are very different from each other, those interviewed seemed to share the same concerns, the same foreboding concerning the current situation of social housing in Quebec City, and they expressed the feeling that a real crisis is upon us. The organizations in question are facing increasing difficulties to meet assistance requests for housing either from people with mental health issues, poor people, single mothers, or even just tenants living in the neighborhoods in full gentrification mode. Confronted with these situations, the viewer was quickly faced with their commonalities, their collective and social dimension, and saw inevitably emerge the question of the “right to housing“. In the light of the psychological impact of housing precariousness, questions were plenty: is housing now reduced to the status of a simple consumer good? What is the true social cost of this situation? Should Housing not be regarded as a fundamental right, requiring appropriate measures?

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

The interest of Michelle Teran’s approach lies in the ability to exceed the uniqueness of the individual experience to make the social dimension emerge, to find the “macro” in the “micro”.

In addition, the perspective of the artist on the question of the “right to housing” is best understood considering other events having punctuated her stay in Quebec City. At the beginning of November, there first was the screening of the film Mortgaged Lives (2013), which documents the resistance movement against the residential evictions that grew in Spain from 2006–2007. Then, at the opening of the exhibition on December 12, the text “Sessions Rupture” which were the transcript of a conversation between a psychologist and four female victims of an eviction in Madrid, taken from the movie Mortgaged Lives, was read by as much of participants and participants invited for the occasion. The discussion that followed this public reading showed very well the effectiveness of the approach of Teran. With some exceptions, the Quebec public does not know exactly the context of origin of this conversation; the circumstances of the crisis of the evictions in Spain, which passes under the radar of the local news media, of course. But it is precisely this lack of familiarity which produces the effect of abstraction allow to reveal its universal dimension, and to bring attention to the traumatic psychological dimension of the experience of the eviction.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Let us Gladys words—one of the victims of this crisis of residential evictions — , to be perfectly understandable they need to be provided in relation to the Spanish laws on mortgages, but who cannot fail to resonate with most of us anyway:

“On the phone, by mail. Whenever you open the letterbox, it’s like an emotional blow. What do I do? If I don’t have the money, how can I repay the bank? And the bank will take it all back, until there is nothing left for me. And then they will tackle my family. That’s what hurts. It’s a mixture of feelings. Fear. State of distress. Anxiety.”1

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

The ensuing discussion easily engaged on the parallels with situations experienced in Quebec, on the traumatic effects of the loss of our housing, of our “home,” and on the cycle of anxiety, the sense of guilt and despair: how those feelings that can be spontaneously perceived as individual weaknesses actually exceed the level of the individual and are part of a mechanism whose result is the strengthening and the legitimation of social inequalities.

Michelle Teran thus managed to show how difficulties experienced as individual situations are actually the effects of a system that operates all the way into the soul of the individual. How people who know these difficulties, and which according to the dominant discourse would have only themselves to blame, are actually the victims of a process that tackles their self-esteem through invisible channels. How this system leaves traces, indelible scars. And how, finally, several people are able to find the balance, confidence, or the necessary pride for the pursuit of a somewhat peaceful life in the action, either by militant action, community work, or simple gestures of mutual assistance. Let us continue with Gladys:

“Then what we did it is to make visible their ways to hurt us. To make it visible, it makes us strong. It’s true. […] I have this idea that they will have to give back what they took from all these families; even if it’s only a part of what they stole. It’s a crime.“2

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

This residency in the fall of 2015 marked the second passage of Michelle Teran at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, and the continuity of her work on social trauma in urban space should be stressed. In 2006, Teran had documented, using city maps and interviews with passers-by, residents and merchants of central areas, the psychological scars left by the fence installed in 2001 at the Summit of the Americas to make the Old Quebec area airtight to any challenge of the event: a fence reinforced with mandatory pass, the extraordinary police units, the helicopters, tear gas, etc. In this project, the artist didn’t have any trouble to revive among the people in the neighborhood memories this shameful episode, meted out to all the citizens of central areas of Quebec City by the local and international political classes to discuss a FTAA (Free trade area of the Americas).

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

If contemporary artists are regularly faced with the dilemma of unintentionally contribute to the gentrification of old or working-class neighborhoods by the interventions they do, with Michelle Teran, we are clearly dealing with an artist who knows how to avoid this kind of paradoxical situation. Indeed, her work on the right to housing and the psychological trauma associated with the loss of the “home“ rather highlights the harmful effects of real estate speculation and social segregation often accompanying projects of “revitalization“.

- TERAN, Michelle. 2013, Sessions Rupture. Madrid: Psychosocial Impact Group of the Truth Commission and PAH Madrid, 2013, p. 8.

- Ibid., p. 19.

Around Lighthouses from Alice Jarry and Vincent Evrard

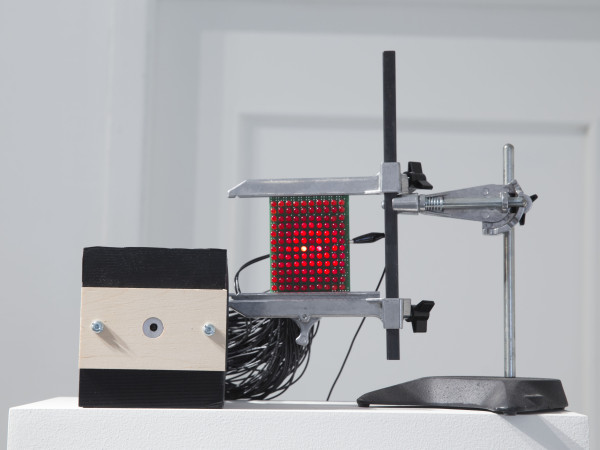

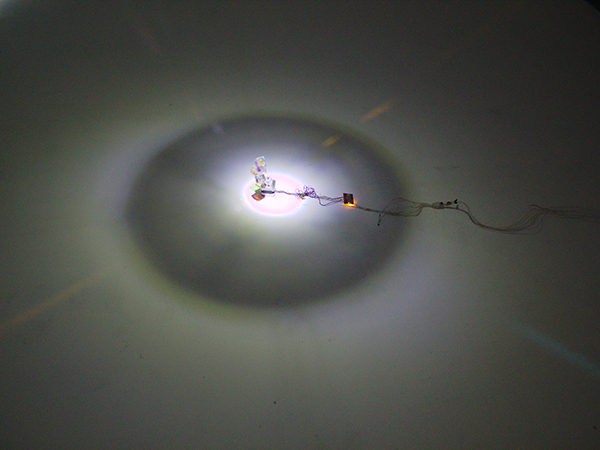

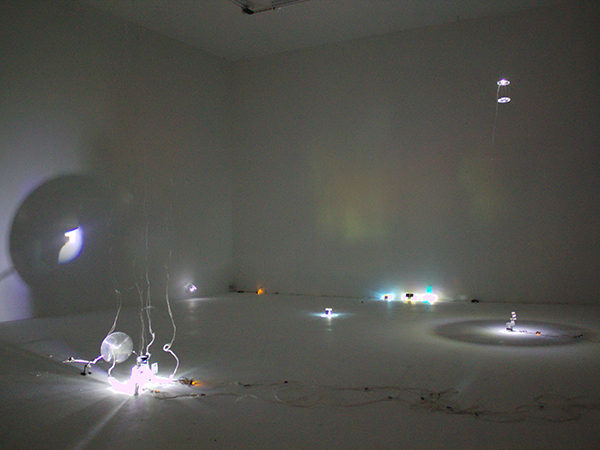

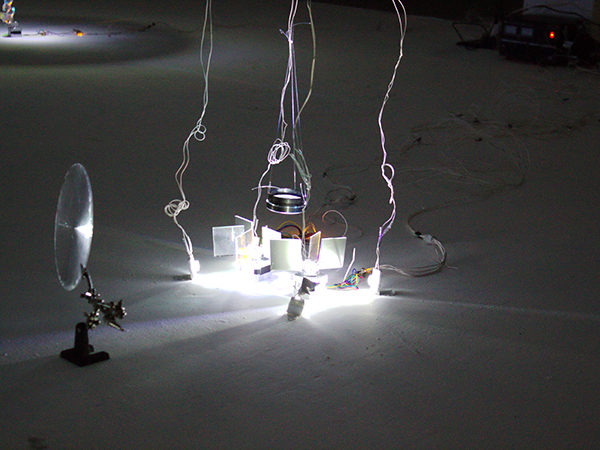

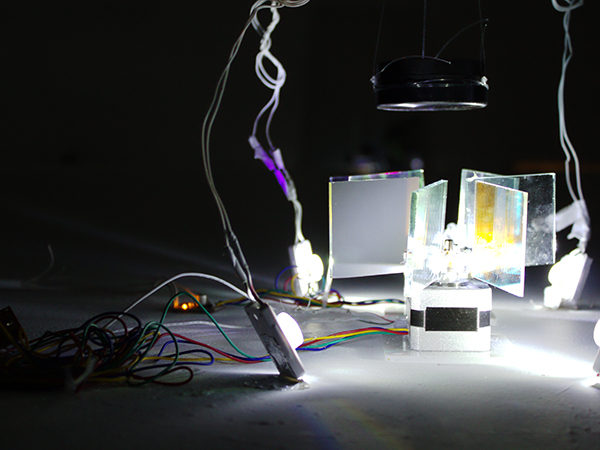

In LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE gallery, multiple light sources are paired with compositions of glass and dichroic prisms, mirrors and photographic lenses. Some items are stowed to randomly set engines in an unpredictable movement, at once relentless and delicate, to deploy light in a changing iridescence, accompanied by the sound of the engines and the clatter of the materials at work. Immersed in semidarkness, the gallery lights up with this series of installations projecting onto all surfaces of the space a polychromatic radiance that roams the room without invading it and continually redraws its contours, just as they react to the configuration of the space.

crédit photo: Carol-Ann Belzil-Normand

Alice Jarry and Vincent Evrard thus put the constitution material of the cinematographic image at the service of a diffractive game on several levels, composing this iridescent constellation significantly named Lighthouses. The phenomenon of light diffraction is here convened at the forefront. Even more, the logic of the diffraction, as a mode of interpretation and interaction with reality, permeates the entire work. Light itself is thus integrated to a dynamic of physical and semantic interactions suggested by its wavelike properties. It does not serve to show a picture or an object to be revealed: but rather, each of these small beacons is a source of light and sound deployments each occurring through others, dealing and interfering from the onset with all the components of the environment, and plunging the participant at the heart of its modulations.

Diffractions

Diffraction is the optical phenomenon in which light rays are deflected and disseminated when meeting the edges of an obstacle, which allows to separate the light into distinct beams of colour and recompose them in white light. Current image projection technologies operate the diffractive properties of the lenses and dichroic prisms, jointly with assemblies of mirrors and lenses. These components are here repeated at new expenses, to be assembled in an unusual, open and dynamic fashion. The installation thus presents itself as a series of deconstructed but functional small projectors, each piece operating according to its own logic in a new and unpredictable composition.

crédit photo: Carol-Ann Belzil-Normand

The diffraction process is thus at the centre of an installation that strips the light of its representative, or mimetic function to let it act in its own materiality, into the very components that daily lead it to our screens. In addition, the installation is not confined to the juxtaposition of a series of small lights spread out in the space. The whole is cohesive, not only according to a specific orchestration, but because the bright deployments circulating in space and the sounds produced by the installations intersect and interfere. Ultimately, the actual encounter of the artists can be understood in these terms: light entering in LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE through the intervention of Jarry and Evrard appears in points of meeting resulting from the interaction of their approaches.

A meeting, notably of a sensitivity toward the singularity and the power of action of the matter, and attention to the constitution process of the meaning and the narrative.

crédit photo: Carol-Ann Belzil-Normand

This approach is part of the method of diffractive reading developed over the past two decades, particularly by Donna Haraway and Karen Barad. While the optical phenomenon of reflection structures the classic paradigm of knowledge, according to which the truth of representation depends on its resemblance to the original, the diffractive approach lets us learn how to think following the logic of the deviation and the diffusion of light waves.

Indeed, these produce illustrative interferences, such as the objects encountered as well as movements of light itself. To the discourse on materiality, the diffractive reading prefers the entanglement of the materiality and the discourse. To the knowledge understood as the adequate reflection of objects kept at a distance, it prefers knowledge experienced as a concrete practice of commitment in the world. It seeks to account for the significant meeting points between the materiality of things and the sense with which they are invested1.

The Reality of the Image

In this frame of mind, the film screening materials are here put in action in a way that dissolves the usual frontal quality of the image. This image is a statement of a reflective logic: the image must be a mirror of the original; either the most perfect representation of an idea, the faithful imitation of a reality, or at least some of the traits of said reality for the benefit of the success of an illusion. Thus, ultimately and perhaps paradoxically, the successful illusion– therefore the image resembling reality- tends to dissolve the identity of the viewer. This one, absorbed by the visual and sound show deployed in front of him, loses and forgets himself in it. That is not the only thing of course, but it must be clear that the omnipotence of contemporary film and video are of this order: they catalyze the viewer’s renunciation of his commitment in reality. Thus, the image is used to not see, to not take a stand.

Here, rather, the spectator necessarily becomes a participant in meeting with the materials that constitute the image itself. The staged light does not intervene as a neutral agent erasing itself in the revelation of the objects rendered visible. On the contrary, it reveals itself, shows itself at the same time as the bodies that it enlightens, and which in turn modulate the trajectories. The shadows, on the other hand, do not embody the simple negativity of the absence of the visible. The body as an obstacle acts not only to stop the light, which draws the negative silhouette of the obscured object encountered, but also by diffraction, as a sign of its wavelike and polychromatic properties. Similarly, the rattling and shocks underline the materiality of the image often associated with a kind of immateriality of the light. The light itself, beyond its ethereal nature, thus appears in the work of a materiality which acts upon the bodies that show themselves by reflecting it, absorbing it, by blocking it, etc. In addition, the technical devices implemented are visible. As much as the movements of the participants, the intervention of the artists is apparent: wire and engines are part of the whole. Present in these traces, they withdraw yet at the last moment to let chance decide the movements of the engines.

Crédit photo: Pierre-Luc Lapointe

The play of the projections thus deployed does not favour the dissolution of the viewer in the image. In this dynamic where light, materials, shadows and people are moving together, no posture allows the participant to ignore its position. It is always immediately and visibly active. The passivity of the viewer that is assigned to a position of receptivity is undone to push him into the co-constitution of forms deployed in space. Indeed, it is impossible to access the installation without affecting it. Necessarily, the light beams meet the body of the participants, whose shadows interfere between the shapes projected on the walls. Similarly, the sound of their steps, the sound of their breaths, and even their words meet the rattling glass ringing in the space. The viewer becomes a participant while he meets the materiality of the cinematic image in a way that forces him to reinterpret and recompose his rapport to it, to respond to the movements in which the image works itself around and through him.

The Little Light

As he takes part in the installation through his body and gestures, the participant also enters inwardness areas. The installation, by the separation of the light and the effects of chiaroscuro, creates an intimate and reassuring space bringing him back to himself at the same time as it directs him in space. Here the show’s externality and the inwardness of the consciousness are crossing. The effect is not unlike the pages of Gaston Bachelard on what he called the musings of the little light. These are foremost, for the author, inspired by the flame of a candle, flickering fragment of fire, carrying the observer in the familiarity of a quiet reverie: “In all, the chiaroscuro of the psyche is daydreaming, a quiet, soothing reverie, which is faithful to its centre, lit in its centre, and not tightened around its content, but always somewhat overflowing, filtering its light into its dusk.”2 The installations are reminiscent of such a description: light sources spread around themselves their soft iridescence, exercising a kind of force of attraction and fascination.

crédit photo: Pierre-Luc Lapointe

To Bachelard, in fact, the electrification of the lighting has resulted in the loss of this intimacy with the light once provided by the candle. Yet, here the bemoaned effect of the flame flickering in the night of a pre-industrial time is now met through technology itself. Material vectors of the flight into the image thus bring the participant back from the distant to the close, from the externality of a represented world to the proximity of an inhabited world—or one to be inhabited.

Horizons…

If the Lighthouses of Jarry and Evrard guide us, it is not in a way to indicate a destination. This technological constellation shifting and deployed in the same space we roam does not offer a stable and distant landmark dictating the direction to take. It rather accompanies us in our movements in a way that etches them at all times in the materiality of the visible: at all times our place is shown to us in the changing configuration of the space. Lighthouses thereby makes us meet the traces of our participation in the reality of the cinematographic image, precisely at the point where we have the habit of forgetting ourselves. Through these paths there is a consolidating experience revealing that the cinematographic illusion is not in the projected image, but in the separation of the passive viewer who would remain a neutral observer.

- Barad, Karen. 2007, Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham and London : Duke University Press, p. 86 et suiv.

- Bachelard, Gaston. 1961, La Flamme d’une chandelle. Paris : Les Presses Universitaires de France, p. 17.

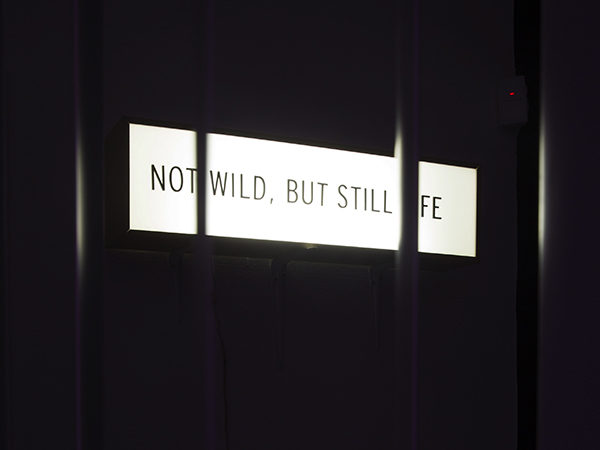

Not Wild, But Still Life

In the fall of 2014, artist Nancy Samara Guzmán Fernández, along with teammate Rodrigo Frías Becerra, initiated a research residency on the bureaucratic system of the city of Quebec. The Édifice Marie-Guyard on Grande Allée avenue, the highest office tower in the city, was the location of their prospecting. Housing various ministries (Ministry of Education, sustainable development, environment and the Fight against climate change) this huge skyscraper overlooking Parliament Hill is a place where every day, different political strata evolve.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

In her exhibition Not Wild, But Still Life, Samara invites the viewer to discover this administrative architecture through a personal interpretation of our diplomatic apparatus. Samara’s work questions the place of the individual in the political system. A work, which is based not only in Quebec City, place of production of her research residency at the chambre blanche, but also in her native City of Mexico. In her attempt to articulate a reflection on various countries bureaucracy and thus create a configuration, the result of her work in Quebec is imbued with a strange dreamlike atmosphere where remains a note of sadness. This impression of melancholy comes from the Samara’s desolation in the face something that happened in Mexico in September 2014: it casts in LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE gallery, the mourning and the grief she feels at the disappearance of 43 students of her country and of the Government’s carelessness towards the situation. The research she has undertaken in the Édifice Marie-Guyard during the night, takes the form of a performance in which she pays tribute to the missing students. She tells us, by the darkness in which she plunges us, the absenteeism of the judicial system and the lack of interest of the Government in the evolution of cases. At the same time, she captures different symbols and images presenting the course of her experience inside our own bureaucracy.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Initially, what her immersion in our political reality reveals, is not only its rational organization, but also the way human life is ordered so as to make our institutions “habitable”. Samara reflects the weakening of the state mechanism by the integration of the “living” in its project: Not Wild, But Still Life. Bureaucracy, this inherent fraction of the Governmental apparatus, is a place of organization of society, a location of translation of existence into documents, numbers and words.

The “living” becomes apparent in this exhibition by the deployment of a particular ecosystem that comes alive in an offbeat atmosphere: representations of plants decorate the environment and give life to a functional workplace, the black and white photocopy of a clock seems to stop time like a suspended dream, vertical blinds reflect the neon lights at night and create shadows where we imagine beings locked in cubicles.

This wild state denatured by the context in which it exists, questions the place of the bureaucracy and the impact of its functionalism on existence. LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE’s gallery is remodeled into a reinvented office, the stereotype of the robotic civil servant turned into a disturbing vision by the duality between the wilderness represented, and the automation of a complex built system. Flaws, crumbling, interfere in the structure in place, questioning it, weakening it.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

The symbolization of the bureaucracy in the work of Samara leads us to reflect on the methods of governance and on the direction of the ministerial system dedicated to the edification of premises assigned to the organization of society. She furthers the reflection on the application of legislation to manage human existence (laws and standards) as well as on the operation of technological and media systems (television, radio, internet) which are now integrated to our private lives, our hobbies and our habitat. Michel Foucault names this exercise of power upon the citizen, the biopower. This sliding of the Government into reality settles in “bureaucratic” structures which are used to quantify, qualify, handle and capture the characterizations of a people in order to facilitate its governance, but also to keep it in the dark with the help of the administrative complexity. According to Samara, the political system appears to make the people feel secure, however it keeps it in a heavy regulatory world not easily accessible by the citizen. The Government apparatus consists of a system of justice, laws, standards, educational institutions, media, all kinds of ministries, disciplines and internal coding that complexify bureaucracy by cumbersome procedures.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Several journalists have compared the work of Samara to the literary works of Kafka. In his existentialist books, the author transports us to a world where realism and irony come together. The bureaucracy appears as a strange masquerade inside of which the main characters, often of ingenuous citizens facing the workings of power, experience absurd and hopeless situations in the face of a burlesque-like justice. Samara’s work transports us to a similar world, on the edge of absurdity, where there is a duality between the primitive and the predetermined aspect of living in society. We are immersed in a night without end with the impression of only see the part of the bureaucratic reality they want to show us. Samara invites us to question the aspect that justice can take just as Kafka in his book Le Procès (The Trial), that translate the deceptive power it holds over the citizen: “justice has a strange power of seduction, don’t you think?.”1

-

Kafka, Franz. 2009, The Trial. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 256 p.

Coming Soon

Coming soon

Božidar Jurjević

Boom!

A terrible noise, something just happened. It’s the signal… a flash, then the explosion. Everything is triggered. A great explosion: the fuse had been burning for a long time. Now the revolution has started.

Božidar is an athlete: He’s in training to live and over the years to survive. Each morning, with Spartan discipline, he fights gravity, wrestling and resisting the fatigue and the dust. The weights fall to the ground, walls tremble and ropes are tightened. The noise is deafening, at times mysterious. The training is meticulous, planned in advance, like an athlete preparing for the Olympics. His body and his heart must be physically, muscularly ready to withstand the trials of his performances. The revolutionary must be ready to bring the walls down. When there is no air to breathe, the artist must not get out of breath. He must know how to catch his breath in a reflex gesture, like a swimmer, even if the environment is hostile and unfamiliar. In this event, there is no place for error: one survives or one dies! One must be ready for battle. Ready to use the sweat of one’s brow, to roll in the dust, pull ropes, move walls, be ready to call the shots and to begin again and again and again. The artist leaves nothing to chance because the revolution is about to happen.

Božidar is a traveller: Ideas for a revolution don’t come to him all at once. He must nourish them; let them ripen in order to finally use the fruit. The trip, the other, the encounters, the differences nurture the artist. These are grounds for expression and prime material for his imagination as one could see in Zaragoza in Spain and in Quebec City in Canada. The trip leads him to become a “digital tablet character,” a sort of personification of his inner thoughts produced in Quebec. He works for months, preparing, testing and finding ways to give expression to his ideas. The artist travels and makes his ideas travel. He must be constantly on top of his game in order to produce. He needs to encounter the other to ask for his/her viewpoint, opinion and advice. Thus Jurjevic’s revolution is being prepared: mentally and physically.

Božidar is neutral: As surprising at this may seem, the artist has chosen not to be associated with a particular colour or state. Let us say instead that he knows how to change and use camouflage according to his objective and the environment. Not supporting a colour doesn’t mean he doesn’t have conviction. Because every revolution is stained in blood: experiences in life have shaped him so that he chooses not to display a flag. He simply wishes not to carry a standard that would associate him with a religion, too restrictive for his taste. He doesn’t want to be associated with a political party in which corruption undermines credibility. He no longer follows any particular belief: inspiration is his best ally. The artist however has the conviction that man can do better, can go further, can be better and more beautiful. There is no point in being labelled, like the remains of the burnt flags illustrate: his standard after the battle. In reality, one must remain revolutionary in the service of the people and the majority.

Božidar is a combatant: He has been as close as one can get to fighting. He has become more aware in the heart of the fog to better broach it, to evaluate it better. The artist has seen the animal side of man incapable of self-control, of excelling, of becoming human in the service of his family, his community and his people. He has seen the greed and all the human absurdity. In the blood bath, he understood suffering. In the mud, he understood the ground. In the fog he understood where the light was. The revolution has become his theme, his vision. He was in the trenches on the front line during the fighting. He saw the bad. He did well. He has chosen the good.

Božidar is a worker: The corrupt political systems have given him inspiration: the ideal seed, the pure makings of a revolutionary. Power makes one thirsty, power calls, power increases but power darkens, breaks up, deteriorates and makes one deceitful. The corruption in political systems inspires Božidar, gives him fertile ground that is limitless and constantly repeated by man the animal. A capitalist carnivore too powerful for his adversaries, stuffed full, no longer having any appetite. But the artist has chosen the people. This crowd that has a craving for truth about the government that enlisted them. They will know in the end, through experience and by disposing of the monarch with blue blood. However, it is actually red, the blood flowing on the cloth around the monarch’s neck. In the end, the people know through experience, learning and discovering the nature of the monarch and his henchmen. The artist has matured: become more aware, more realistic and closer to reality that is complex and in constant flux. He is now a master.

Božidar is Croatian: His country has made him who he is and all that he has become. He loves his country: he’s patriotic. He hates his country: he’s a deserter. Some would say a revolutionary. He wears the colour of blood, the red that guides the revolution and the blood of innocent martyrs who fall in combat. He has not chosen an ethnic group because his concern is man. Division exists only through the roles that we decide to take on and keep. He has decided to fight against the forces of nature. Strong natural elements, elements that are naturally sound. “The system is awful” he began by telling me. Nature is beautiful, I thought. Do you dare defy it?

Boom!

In a revolution, everything begins and ends with an explosion. A deafening noise creates chaos and disrupts the order. There is nothing left to burn, nothing more to consume. The protagonists are tired. They must regain their strength for the next battle. Seven blocks of ice, seven protagonists are frozen and petrified by the battle. Each one in his block recovers his strength before the next thaw, the next human carnage. Awful…

Cabinet of Time

Bruno Caldas Vianna makes traps that capture time. The devices that he creates are produced from technological equipment that is considered out-dated. He acknowledges that the exhibition he presented at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE could evoke a cabinet of curiosities or even the Wunderkammer, “the room of wonders.” Gathering together equipment that has now become obsolescent, the artist’s process resembles that of someone who collects curious objects. Instead of preserving them in a set time, Vianna gives them new life, attributing new functions that are provided by the immediate environment in which they are found.

Dependent on noise, movement or light, Vianna’s creations transmit bits of reality that come from the specific devices. Their reassembly gives us the impression that we are able to simultaneously perceive the world various ways. Rather than presenting differing scales of it like a magnifying glass or a telescope would do, these are fragments of time that are captured.

Certain of the device consist of new interpretations of the camera obscura or pinhole camera. One of them was set in motion with the movement of a wheel activated by daylight. Installed on a window, overlooking rue Christophe Colomb, it captured brief moments of exterior light. The resulting photographs, isolated from their initial reality, are presented as fragments of the neighbourhood. Their small size and the re-transcription of the surrounding area that they provide recall Brassaï’s ideas, which considered photography to be made up of “a true but miniaturising copy of the exterior world.”1

For Vianna, the idea of working with the wheel was inspired by the first cinema recording and projection device, and also by medieval engineering. The artist considers that it is initially this choice of evoking old systems that relates the presentation of his works to those of a cabinet of curiosities. In referring to old processes, the artist captures present time while making allusion to the universal history of the world. The rudimentary nature of some of his machines is closely akin to the archaism of the outmoded processes that he evokes.

Following the analogy that Vianna establishes between his work and the cabinet of curiosities, one could compare these images to reduced versions of the world, formerly recreated in scholarly collections and exhibited with the intention of explaining something. In the 18th century, under the influence of Diderot’s ideas that recommended establishing an “encyclopaedic dictionary of the human spirit”,2 these collections were often elaborated, with minerals or plants in order to reconstruct the conditions in which the specimens were found in a living state. It also could happen that various species were grouped together to simulate an interaction that never existed in reality. The little known parts of science then were filled in by the collector’s imagination. Strange coincidence, in order to talk about his work, the artist frequently uses expressions associated with acts of predation: he describes his works as “light traps for time” and compares himself to a “hunter” tracking his evanescent “prey.”

However these moments, even once “captured” and exhibited, are not subjected to the deadly representation usually created by a museum’s immortalization. Because these works depend on the environment in which they are found, in experiencing them, it is the direct capture of time that one witnesses rather than its interruption. One of the devices is used to put together images from ambient noise that is captured in the exhibition gallery. Appearing progressively on a digital tablet, these images present the archaeological interventions made in the city of Rio. Various strata from the distant past resurface due to variations in time, thus producing a revelation of the past in the present.

Another of the devices, reinterpreting the camera obscura, is used to capture various moments of a subject on the same photosensitive surface. The surrounding urban landscape then is revealed in many fragmented moments. The ghostly images are presented in the negative because their capturing is imprinted directly on the paper. These are the variations of light that show the plurality of the moments of the day, coexisting in the same image. Their demarcations recall the erosion of the ground, which shows the passing of time in an area. Unlike a photograph that results in capturing a single moment, this plurality of instants of a same subject presents a version of the world in which time would be abolished by its reduction.

Because Bruno Caldas Vianna’s devices present various forms of capturing time, bringing them together in the same space opens up the perception of infinity in miniature.3 If the obsolescence attributed to components of the works give the impression that they are out of date, it seems paradoxical that these objects now artefacts, contribute instead to providing for regeneration. On the other hand, the time period that this material comes from is not so long ago. By their simple material presence, this collection of various pieces seems to indicate the world’s acceleration, outmoded by the speed of its technological and media evolution. Consequently, there is very good reason to consider the ensemble as a kind of cabinet of curiosities, which has been adapted to the knowledge and imagination of a time, requiring more exploring and understanding.

- Brassaï. 2001, Proust in the Power of Photography. Trans. Richard Howard, Chicago: University of Chicago press. p. 33.

- Davenne, Christine et Christine Fleurent. 2011, Cabinets de curiosités: La passion de la collection. Paris: De La Martinière editions. p. 16.

- Ibid., p. 66.