What another has seen fit to throw away, you must examine, dissect, and bring back to life. A piece of string, a bottle cap, an undamaged board from a bashed-in crate––none of these things should be neglected.

– Paul Auster, In the Country of Last Things1

Object hunting: this is the task that awaits the Anna Blume character when she crosses the threshold In the Country of Last Things. As Paul Auster depicts it, objects occupy a central place in the world that is ending because they are very rare and consequently so precious that it becomes hazardous to throw anything away. Scavenging becomes a way of life and although Anna Blume could choose to keep the objects and pieces of things that she finds, she sells them instead to the city’s Resurrection Agents who convert them into new goods and sell them on the open market. If all kinds of things and all sorts of motives exists for collecting objects, if their gathering is at times carried out as a survival instinct or if it then becomes a form of expression, in any case, it indicates a state of being completely alert to the world just as it tells of a certain relationship to it.

For Le poids des objets the project that Raphaëlle de Groot began in 2009, she gave herself the task of collecting objects that people no longer want and that are found at the back of drawers and at the bottom of cupboards for want of being disposed of. These objects then come from the private space and enter the world of the artist who makes a collection of them so that they can resurface in her work. Far from being a passive activity, the collection for Raphaëlle de Groot becomes a genuine performative act. This is because through her artistic practice, she “redefines” the accumulated objects and gives them a new context for existing. The collection becomes an entity in which things can happen, and is a place for actions and interactivity: ideas of the past, present and what is to come emerge freely through images and performances.

Her collection is made up of a group of objects all more unusual the one from the next, as much for their origin as their history: handles, cabinets, cookie jars, tea pots, straw baskets, storage bags, record player, telephone, wooden shoe, plastic flowers are now her property. Each of the specimens carries its past with it. In fact she collects what people give her and does not screen her collection because the beautiful and the ordinary – if no longer of use – find their way to the artist.

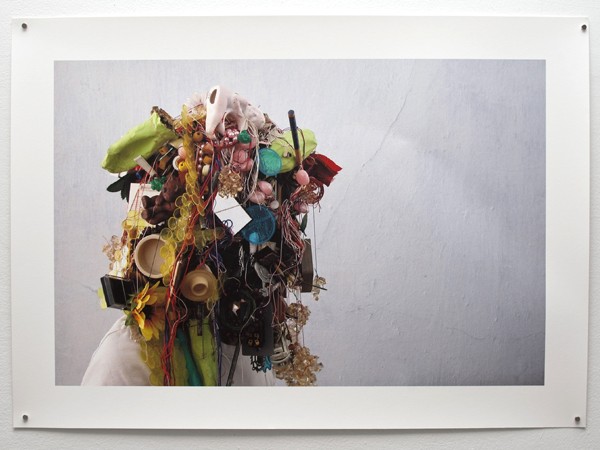

But for Raphaëlle de Groot, thing are not “exempt from the task of being useful,” to repeat the words of Walter Benjamin2 for whom the collection became a permanent fixture that accompanied him wherever he went.3 With an intention other than that sought by the philosopher, the artist also makes her collection occupy all kinds of places and spaces when she transports them on her journeys and to her residencies. Her collection is permanently moving and no place contains it nor retains it. She literally puts it on and wears it, her body becoming the support and the vehicle. It is enough to look at the photograph 1273 petites choses inutiles to see the extent of it: the artist’s face literally disappears under the mass of tied up objects. The collection becomes image, so to speak. Just like in the video Porter in which de Groot, dressed up in her objects, walks around in nature, stopping to eat and rest and then moving again, continuing on her way always all loaded up. The artist continues to put herself physically to the test with the accumulated material – that becomes a language – and she seems this time to want to experience the very notion of collection through her wanderings, revealing how much this becomes an extension of herself. One should always collection oneself Jean Baudrillard already affirmed in his seminal work.4 The collector then should be his own collection and should change with it. But the version that Raphaëlle de Groot proposes shows instead how the collection adapts to her practice and closely fits her wanderings throughout the world. Notably when she passes through security systems when she is travelling, checking in at an airport with a suitcase containing 70 objects that have no apparent use, and to then have them wrapped up in cellophane tape for her return. This is what she placed in the centre of the gallery at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE in the winter of 2011, the bundle of objects presented as proof with its YUL ticket intact.

The artist thus directs our attention to the complex system of transactions with which she surrounds her collection. A new stage in her investigation however has taken form during her residency: that of research and indexing. A list on the wall gives an account of the comparison exercise that she began with the Museum of Civilisation’s collection. Here she draws a parallel between the objects that have been passed on to her – that are now her responsibility – with those that have been placed in the institution’s storage and that attest to the “daily life” of the Quebec people. She now is busy creating comparisons, detecting resemblances and identifying common denominators. A legend at the bottom of the list expresses her thoughts through coloured highlighting and reveals numerous similarities. The interest in each of her objects is communicated here through their association, as if the artist is endeavouring to reveal them to us differently. She emphasizes the uniqueness of each of her “specimens” and goes back to their distinctive features to study the details. Because the objects that she keeps “code” a human experience, she is now the guardian of this incredible ensemble that is lodged there. The storage space is now her new workspace.

Thus, Raphaëlle de Groot’s uses neither showcases nor display cabinets to exhibit her collection-work. Her presentation instead is repeated in each case, this being a matter of photographs, performances, videos, lists, bundles and collector cards. Through her research, she has shared the same burden as that of all museums: the possibility of understanding reality through preservation. No load seems too heavy for the artist who, relentlessly, composes with the proliferation of things and following the example of Anna Blume, becomes a ragpicker of leftovers and recyclable items.

- Auster, Paul. 1988, In the Country of Last Things. New York: Penguin Books, p. 36.

- Benjamin, Walter and Peter Demetz. “Paris, Capital of the 19th Century” 1978, in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 348 p.

- For this see Jennifer Allen’s forward to Je déballe ma bibliothèque, Paris, Payot & Rivages, 2000, p. 7-31. The author tells of Walter Benjamin’s years in exile when he was obliged to leave Germany in 1933 because of the Nazi Regime. She relates how difficult the decision was for him to leave behind a part of his collection of books that his friends would endeavour to save from destruction.

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1996, The System of Objects. London, New York: Verso editions, 205 p.