From Duchamp to Korzybski, from Magritte to Heidegger, many 20th Century artists and thinkers have sought to demonstrate that the act of attributing fixed definitions to things is reductive. When a pipe is painted on a canvas, it becomes a painting. When a urinal is titled, signed and then exhibited in a museum, it takes on the status of a work of art. Each thing has multiple possible definitions, according to the context in which it is placed. And so the work of the Dutch artist William Engelen, at the intersection of visual art, architecture and music, involves displacing the semantic charge of diverse structures by “recontextualizing” them. Thanks to models, architecture becomes installation; by means of a key, calligraphy becomes musical notation. The structures that Engelen uses often come from the substrate of his own daily life: calligraphy from a book in his library, an electro-retinogram of his right eye, a diary from his time in a foreign city, etc. As well as being integral parts of his work, these forms of substrate constitute the basis of his extrapolations and of the core ideas at the heart of his multidisciplinary practice. For example, certain verses written in Arab in the Book of Suleika, as well as graphics representing the electrical responses of the artist’s eye to stimulation by light (an electroretinogram) constitute visual structures within a symbolic system that transmutes them into musical notation. In 2003, this neumatic1 musical notation resulted in the works Suleika and Augenblick. One might say that these works are a form of sound journey shaped by visual structures.

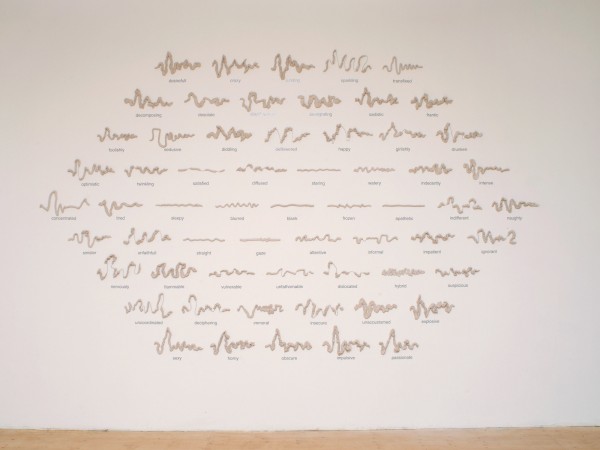

In the early days of his residency at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, Engelen hung two versions of Augenblick on opposing walls in the space. The first version was reproduced in clay, and the second printed on paper. For this work, Engelen had used the 61 graphics resulting from the eye examination mentioned above (the electroretinogram). Each graphic became a neume, intended to convey the character of a melody to a trombonist. The vertical axis of the graphic represented the sound register of the instrument (high/low=high-pitch/low-pitch) and the horizontal axis, the time signature (and so the rhythm). The artist had adjusted the thickness of the lines of the graphics in certain sections, in such a way as to indicate variations in volume to the trombonist. The artist had also written terms relating to ways of seeing the world on each of the graphics, for example “happy”, “crazy” and “desireful”. These ways of seeing the world indicated to the trombonist the spirit in which to play each of the graphics. Once he had defined his system, Engelen recorded a version of the 61 sections of trombone sounds, which he edited together in a studio. Whilst the first version of the visual component of the work, in clay, emphasized the 61 graphics, the second, printed on paper, depicted this sound collage in the form of a table. A nearby sound system enabled any visitors to LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE who so desired, to listen to the acoustic component of the work. Augenblick is typical of Engelen’s practice in that it proceeds from a single element, which he uses as the basis of a matrix, from which he “telescopes” possible outcomes. And so, a semantic layer is added to the graphics representing the electrical responses of his retina to stimulation by light: these optical symbols also become musical symbols. Moreover, the theme of the eye becomes a metaphoric field, given that each graphic is linked to a means of seeing the world. In turn, these ways of seeing the world become forms of musical notation. The viewer has to find their way around a form of network, using a grid that consists of visual elements, sounds, anecdotes and art.

However, the real war-horses of this residency were the two Verstrijken. Verstrijken is a word that, in Dutch, means the passing of time or a play that is badly acted. For this work Engelen wrote two pieces of music whose structure was based on the contents of his diary. And so this work consisted of an autobiographical substrate. Undoubtedly, autobiography, self-fiction and even confession play a central role in the era in which we live. However, the autobiographical aspect of Engelen’s work functioned on the level of anecdote and play, further to its central role in the structure of the project.

In his Verstrijken Pour Solo Violin Engelen kept a diary from the time of his arrival in Québec, on the 10th October at 19.00, to the time of making the work, on the 11th Novermber at 20.00. He then elaborated a graphic score from the diary, on the walls of the space. At the beginning of the score, he wrote: “I arrived in Quebec City on the 10th of October 2005, from that point Verstrijken starts”. And at the end: “Start of the concert at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE on 11th of November 2005.” The score consisted of boxes marking sections of time, in a range of colours. According to the key that visitors could consult on the wall, these colours represented four categories of activity: blue for sleeping, red for eating, yellow for working, and green for free time. A number of recurrent sounds corresponded to each colour: the blue predominantly consisted of sustained sounds, the red of pizzicati (pinched chords), the yellow of bowing and melodic sounds, and the green of sounds of bow-strokes, and forms of pastiche. The day and the hour corresponding to each box was marked beneath it, and the duration of each was written above it. Engelen’s diary, which spanned a month, had been scaled down into four seconds of music for each hour of the day. Thus, the work lasted 51mins and 20 secs. Visitors could see that on the 14th day following his arrival, at 02.30, or 19mins and 42secs in to the work, Engelen had had “no problem to sleep after all those beers.” This example illustrates well the anecdotal and playful tone of the autobiographical aspect of the work (the tone of which was much less “engaged” than, for example, the romantic I…) Each of the boxes allocated to a section of time contained a range of notation addressed to violinists. Some of this notation was neumatic ( a pizzicato followed by a vibrato was indicated with a full-stop followed by a zigzag), and other parts were textual (“play fading tones”, “different pressure on bow”). There were also terms relating to the tradition of classical music in the West, for example “un poco agitato”, whilst names of composers could be interpreted as an indication to imitate their style (“Ligeti”). At certain points, viewers could read extracts from his diary (a green box read “walking on Mount Royal”, whilst a yellow box read “pasting letters on the wall”). On the evening of the concert, the violinist Clemens Merkel, who was to interpret the work, had a condensed version of the score, whilst behind him the public could view the larger score on the wall. Given that Engelen’s system of notation included no precise indications about volume or rhythm, but constituted instead a form of global mapping of a morphological journey, it is important to underline the importance of Merkel’s role in the Verstrijken for solo violin.

Engelen used an almost identical system for his Verstrijken for a trio of strings. However, in this case, a diary was kept, for a week, by the three interpreters of the piece (Caroline Béchard, Anne Morier and Suzanne Villeneuve, from the Quatuor Cartier). Naturally, their diary contained references to numerous hours of rehearsal, dedicated to the works of composers such as Handel, Puccini and Gougeon. Consquently, this Verstrijken contained several musical extracts, selected by the musicians, which they had listed and memorized (the musical extracts were identified only by means of the title, or the name of a composer, for example Madame Butterfly or Gougeon). Once again, it is important to stress the significant contribution made by the musicians interpreting the work. For this piece, which was much shorter at 8mins 24secs, no score was on view to the public, although an extract was displayed on the wall at the entrance to the space.

The notion of using a succession of boxes marking time, with sounds that convey fairly distinct categories, is reminiscent of the work Momente (1962-1969) by Karlheinz Stockhausen. In this piece – with a score that includes boxes filled with drawings that represent sound – Stockhausen explored his theory of Momentform, or forms that sculpt time based on certain distinct features of sound, that alternate according to a diverse range of juxtapositions and timespans (the conductor can choose the formal schema, based on certain rules). However, above all, Engelen’s work evokes John Cage’s compositions, for example Roaratorio: an Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake (1979). For this work Cage read aloud James Joyce’s novel Finnegan’s Wake, whilst musicians interpreted Irish folk music, and loud-speakers broadcast, at random, 2293 noises and names of places mentioned in the book (these 2293 samples were pre-recorded by Cage and entered randomly into a computer program.) Cage employed, as Engelen employs, a substrate (in Cage’s case, Joyce’s novel), as the basis for extracting a range of possible sounds. The approach towards composition in the work is essentially conceptual, removed from traditional composition and craft (for example musical theory, orchestration, and harmony). The works by Stockhausen and Cage include an element of chance in terms of the order in which the sounds occur, which is not the case with Engelen’s Verstrijken. That said, the notation system used by Engelen is based more on suggestion than definition (particularly in terms of pitch), indicating a “decentralized” approach to composition that increases the creative role played by the interpreter of the music. (Engelen requires musicians of a very high calibre). Furthermore, his notation system can lead to significant differences in the piece from one version to another. It is therefore appropriate to refer to the Verstrijken as open works, despite the fact that this statement does not apply to all the parameters of the works.

William Engelen’s Verstrijken project is shaped by a range of disciplines (writing, visual art, music) and numerous problematics in art (conceptual art, multidisciplinary art, site-specific work, open works, inter-textuality, self-fiction). To these is added the structural role played in this project by several aspects of daily life (leisure, mealtimes, work, sleep). As in the majority of Engelen’s works, the two Verstrijken create the impression in the viewer of intersections within a network of clearly defined categories. These intersections propel the spectator into a comparative form of reflection, which may bring about a reconsideration of the grids and definitions involved. Is such a reflection itself an electro-retinogram?

- Neumatic notation, neumes: neumes are graphic symbols that inform the musical interpreter of the character of a melody. In the West, neumatic notation is mainly connected with early manuscripts of liturgical chants from a number of Christian monasteries, from the 9th Century onwards. Neumes give no precise indications of pitch or rhythm. Originally there were used as a memory-aid for musicians who learned to play by means of the oral tradition at the time. In the course of the 20th Century, a number of composers took an interest in neumatic notation, and devised a range of sign systems to give indications relating to melody or, more often, ornaments and sound variations, to complement the traditional musical score.