In the shock of freezing cold January in Quebec City and hardly bothering to plan her wanderings, Gabriela Vainsencher elaborated her project The Unfinished Tour Quebec City from notions of translation and displacement. The wording of her artist’s statement tells us that biographical facts account for her choices and are important in her career as an artist. Well defined as both operating concepts and actions, they have directed the workings of this adventure, that is to say, the ways in which the multiple relationships have become integrated as the days went by and have come to life through the processing of two favourite subjects, the art of others and objects from her everyday life.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

To grasp what is at stake in this project, it is important to consider the abundant nature of the ensemble as well as the sum and diversity of materials and gestures that have composed it, including the artist’s intentions. Also one must continuously pay attention to the various stages as well as to the objects created during the residency process. A first visit to Gabriela Vainsencher’s installation at the beginning, and reading the press releases made me think of Rosalind Krauss’ essay Line as Language: Six Artists Draw1, and I have chosen to refer it in order to go deeper into this reflection.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

In this text, Rosalind Krauss presents pertinent concepts for thinking about drawing, a practice that the artist Gabriela Vainsencher sets out as basic; moreover, both as a process for understanding things and as a reference for when she experiments with other mediums from time to time.

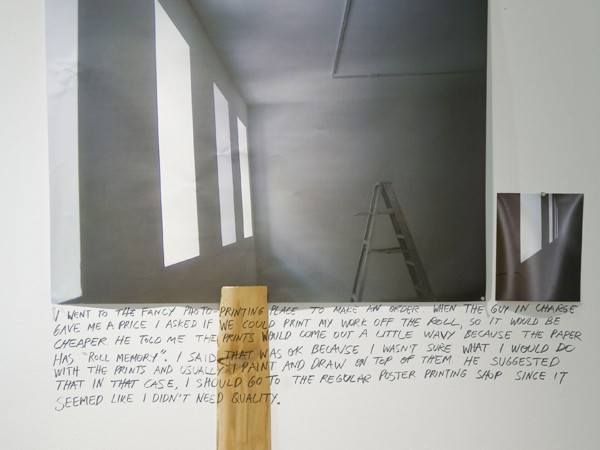

“I make mostly drawings on paper. When I work with different media, it is usually based of the drawings, fulfilling a function which the drawings cannot.”2

The main notions that Krauss favours on this subject are space and expression and here she analyses the drawings of a group of artists that include Sol Lewitt, Donald Judd and Frank Stella, comparing them to works by artists from the American abstract expressionist movement. For me, the idea is not to take time comparing these works with the ones that concern me now. Rather, I am focusing my attention on notions in the text that appear appropriate and open enough to be transferred to a different context, in which the artist’s position counts as much as the place, the installation process and the constructed objects. And what was presented here were Gabriela Vainsencher’s press releases, the very first developments for the gallery at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, her drawing and painting interventions, her photographs, videos and all her manoeuvres, showed the obvious, the profound implication of reality that these concepts cover in her work process, just like the dominating role of drawing. In other respects, not only do these works show compatibility with notions that she has favoured, but also they may include them.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

However, although they are pertinent in their overall meaning, they concern so many artists’ practices of all disciplines that they still do not introduce us to a more astute reading of the project. It is really in resorting to the ideas that Rosalind Krauss proposes in her essay, of an opposition between internal space (the space of a private language) and exterior space (the outside world), and the notion of expression that she associates with them, which opens a way to examine this work without regard for its conformity to one aesthetic category or another. And, more precisely still, the consequence that this idea entails: two quite distinct visions of drawing, one as illusionist projection, also integral to the work of the abstract expressionists, and the other, drawing as a kind of showing this world, the exterior world, a contemporary vision of it. Two visions that define the distinction between artists dedicated to expressing a private myth, let us say, and those such as Johns, Stella and others, who dissociate strongly from it, asserting themselves according to their terms, not in relation to a projected world but in tune with the pulse of this world.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

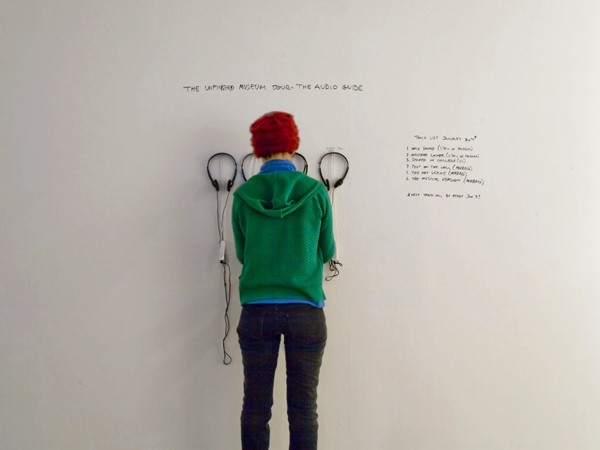

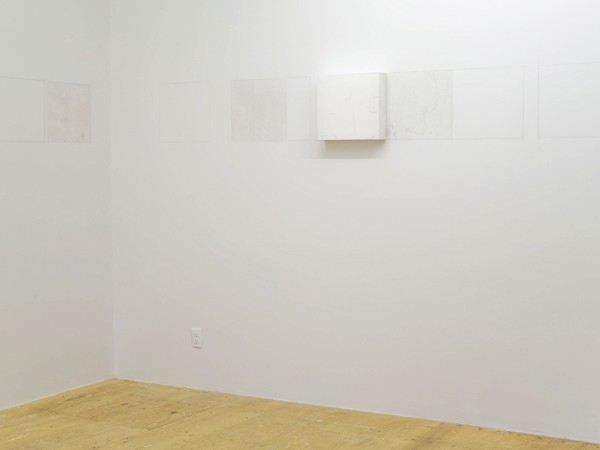

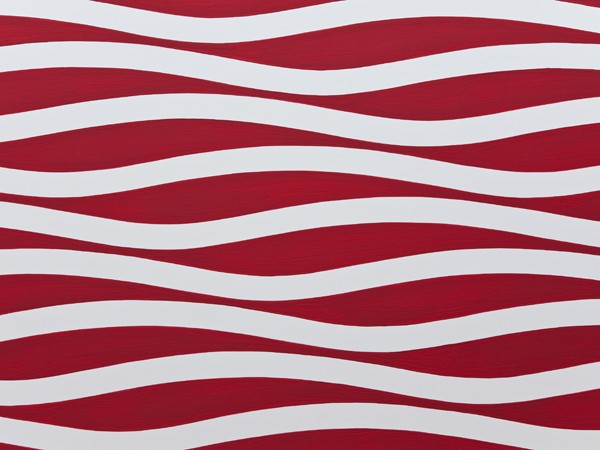

Going from here, it seems interesting to me to see what the elements of the evoked duality require us to consider in Gabriela Vainsencher’s installation, all these concrete visual and sound works that she tells us are constructed from translation and displacement actions produced in the gallery, thinking about the space and the surface areas. For example, this angled worktable in the centre of the gallery is placed in relation to the disposition of the walls configuring the space. A gesture that can be understood as establishing the artist’s position as the centre of the action, a point of departure for comings and goings and also showing the significance given to the place in terms of geography because the direction of the viewer’s gaze depends on the artist, as well as the movement in the gallery. Therefore, the walls are partitioned into several related groupings, each time marked out by the dominant presence of one of the numerous mediums used. By establishing spaces conducive to diverse interventions, the artist thus defines an opportune way of presenting a remarkable feature, the multiplied representation of her designated image, from what one knows to be her image from what she has said, through visual strategies such as framing and point of view, and not by identification. These are visual signs, sounds and representations in one form or another, literally or as evocations coming from plays on language. And finally, introducing an aspect of another nature, but just as significant, the artist shares private moments from her everyday life, stratifying the course of experiencing another temporality, this morning ritual of drawing everyday. Thus it resurfaces that the significance of the artist’s space in the actual framework of the installation is in reality established at the beginning of the Gabriela Vainsencher experience. Since the start, the artist has informed the space, but, and this must be emphasized, she has always integrated the space of the other into it, especially in constantly enhancing the architectural space, as one could observe, and that of the city to which some of the videos refer.

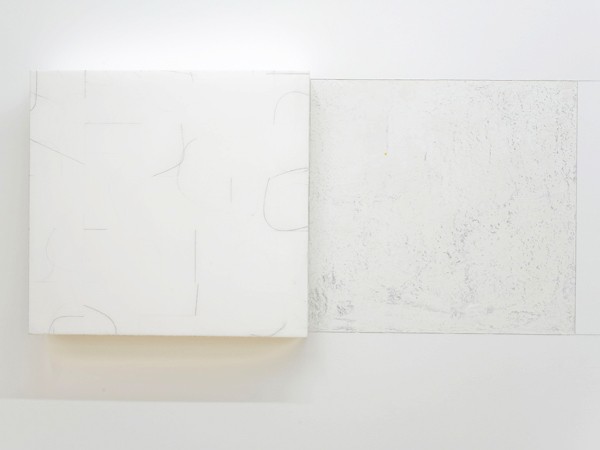

This being so and in remembering my first surveying of the place where the artist was working, I recall my keen attraction to this grouping of work on the walls forming the west-north-west angle of the room. From afar, one first saw a multitude of small drawings pinned to the wall at varying heights and in which the shadow of the lower raised corners often were added with drawn and painted marks. Covered with glazed touches, this produced a kind of quivering effect. One had to get closer to grasp image by image what they were, discovering right away what made them relate, same light-weight paper, similar format, method of presentation, medium and treatment, the same. Then my identifying gaze was activated, looking for relationships in the images, multiple close-ups producing fragments, feet and legs viewed from above indicating the artist, rarely the face however, neither here nor in other groupings, part of a refrigerator, outside views, writing, television set, plants, a pot, a key, a very blue projector, a cable, all everyday things of a socially aware person and artist. And again, this private view introduced us to this new space of openness that presented a great number of these images, space for commentary in which the content really belongs most often to that of a diary both by the variety of the subjects and the freedom of expression. The treatment of all these elements, image and handwriting, revealed knowledge of the effects of paintbrush and water and here a freedom in the drawing, but a facture remaining simple and appearing without the wish to be expressive. Expression without the aim of expressiveness, one could say.

The artist attributes great significance to the actual process, both the ritual nature and certain procedures that she has decided to follow, that for example, of letting all the mistakes show through in the drawings that have been changed. On this subject, she evoked the matter of integrity. This could very well be linked to a very old historical vision of the image as an element of illusion, the false image. One does not know to which time to associate this rule, but the fact is that it introduces an aesthetic aspect that also refers to another side of psychic space, a private space if there is one.

Continuing on the course progressively reveals that this grouping of small drawings makes up an image bank from which Gabriela Vainsencher will draw to present work on the other wall areas. In fact, few of these works will be retained and the result will be to show the few recurring figures, those that especially concern her, designating her as a subject but which, as a result of being multiplied, will end up objectivizing her, an object among the everyday objects. Thus when being a model for herself, the artist produced feet and hands, legs and necks, one after the other, these figures then became motifs and thus thwarted any possible perception of their image status as a portrait of an insistent ego. From then on, she worked increasingly to distance herself as a referent, preventing her identity from becoming important and hence the subject.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

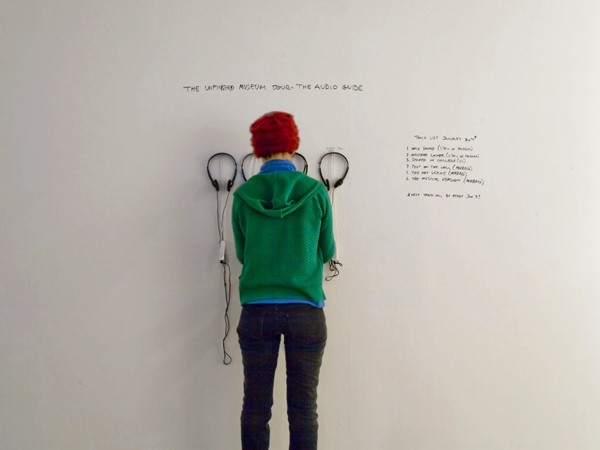

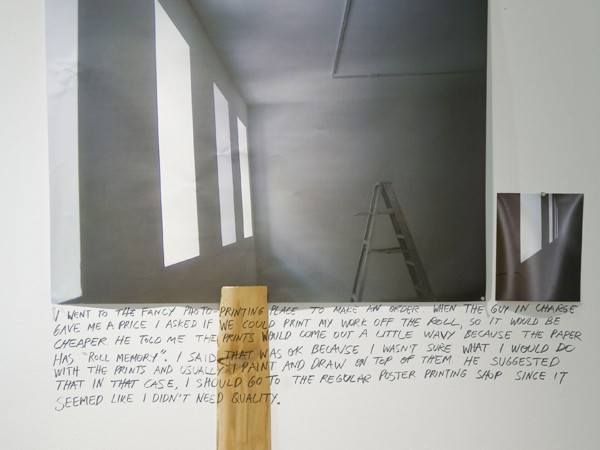

Finally, here it is necessary to recognize the major role of images in relation to the overall residency experience. It must be said that when a figure is presented in one medium, and then in turn, this figure is represented in another medium to produce a translation, another image is created through this transfer. And more than just considering the facture and treatment of the one and the other of these mediums taken separately, it is in their difference that a new meaning occurs. These relations create a force from “the interval,” from “the spacing,” one could say. Strangely, the difference opens another world, describing the specific mode each figure inhabits. Thus, for example, one of them is this hand that one saw as a very small drawing, now painted in large scale, architecturally occupying an area of wall. From this also, from memory, the same hand, but that the video presents in another way, in its action of writing words that appear jerkily as green handwriting, commenting on the work of another artist. Green commentaries that one will recognize in the linked photographs a little further along, right near the hand-drawn plan made directly on the wall of a museum space where the artist intervened. Then again, windows on the windows of the gallery, among other videos, those that capture the feet and legs already drawn, similar to those viewed from above, but moving this time, here in the snow and there on dry ground. And not to forget the auditory component, the words waiting in their iPods, hanging on the wall, vocal thoughts on the visual experiences of other artists’ work in other places. Interventions that also recall this aspect of a diary already observed.

I am constantly calling this residency an adventure. One that is built up through lines, journeys, stories that have taken place, that develop, are close by, are linked, branch out, and weave a network of spaces, objects, figures, sounds, lines and of course time always, at various rhythms. One perceives, among many other things, the structural complexity that could justify many metaphors, from a mille feuilles layered arrangement to a woven “cloth” design or an abyss, often coexisting, none of this being quite right, but even so we always understand that something is continually silent in the coming and going space that Gabriela Vainsencher occupies, which will remain distinctive to her, unsaid, through time.

Private space, exterior space, private myth, real world, all these notions might be pertinent, but we have noticed that in this residency they have not led to the question of duality. Neither have the vast number of expressive gestures about the artist’s personal time and space, constructing network relations of all kinds, been referred to as an end. Actually, perhaps it is the dialogue between images and spaces shown in concrete terms in this work that involves a constantly evolving form in this remarkable combination of worlds…

- Krauss, Rosalind, “Dossier: Le dessin”. 1990, in La Part de l’OEil, Annual magazine n. 6. Brussels, p. 208

- Vainsencher, Gabriela. 2007, Artist Statement. Brooklyn.

Diane Létourneau