LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE felt empty. With the lights turned out, at first sight it seemed that there was no-one there. But only at first sight, because as soon as our eyes ceased searching, our ears picked up the noise of several people in the space: the drumming of the footsteps of a child, above our heads; the soft voice of a mother; a man walking down a flight of stairs. LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE was not empty, the space was occupied by artists who, rather than filling the gallery with images, or with themselves, had been working in the streets, engaging with the people, places and sounds that surrounded them. And so, in the context of an exchange with British Colombia’s Open Space, the artists Kristen Roos and Daniel Jolifee came to Québec as artists in residence, with the goal of developing projects on the theme of The Transmission of Knowledge.

Kristen Roos is a sound artist: he crafts sound sculpture, he sculpts sound, and he is a practitioner of radio art. Between the space of his hands and the spiral form of his ear, objects that are used to transmit particular information witness their function and their form altered. By means of temporary structures, he seeks to transform the way that we perceive the things that surround us.

During his time at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, he took an interest in the heart of the city. He gleaned sounds and testimonies there, inviting us, in his own way, to rediscover them through radio broadcasts. He recorded the pulse of the city: a car starting-up, a lorry reversing, a passing train, a show at a local bar, kids in the parks. Inspired by the ringing of the bells in the numerous churches of the Saint-Roch area, he interviewed the parish priest Réal Grenier, who recounted its ancestry, and the historian Réjean Lemoine, who traced the evolution of the area.

And so, on the evening of the 2nd June, at the launch of The Transmission of Knowledge, we had the opportunity to witness a performance by Roos, during which he played an extract from the sound collage resulting from his experiments. The artist advanced, carrying a small radio, from which came an abyss-like echo, that slowly but surely took on its original form: the intermittent signal of a vehicle reversing. At the other end of the gallery, Roos’s partner Lorraine Plouffe tuned-in a radio-station on which Réjean Lemoine was discussing the Saint-Roch district: its industrial era, commercial heyday, economic decline, the presence of artists, and its revitalisation. These episodes were punctuated by sound interventions. We could make out the sound of a locomotive whistling, which transmuted into a call similar to that of a whale, as electronic alchemy transformed the railroad tumult into an aquatic languor. In contrast to the futurist backfirings of the last century, Roos brought us the groans of machines, and an impression of lyricism and nostalgia.

Whilst the performance was too brief, it was a good introduction to the work of the artist’s residency. The inventory of the material used for the public event was evocative: a small console, a speaker and four pieces of outdated radio equipment, obviously found in a second-hand shop, one of which still bore a hand-written price ticket, and the other of which had had its guts taken out, evidently a victim of a “gadgetting” operation. The broadcasting of a low-power radio frequency demonstrated a desire to use a minimum of equipment, a low-tech approach even. Despite the antiquated tools, the issues remain contemporary, touching on problematics such as the multiplication and the transfer of forms of sound in space. Roos’s project involved working with a team. His partner, who has a degree in social geography, actively engaged in the work, notably by conducting interviews. Thus, the artist erased himself, letting the voices of others be heard: those of experts, as well as those of men and women on the street.

The first morning after the performance, and each evening the following week, different audio montages were broadcast on the airwaves of 97.5 FM, a radio frequency that is not normally in use. During the introduction of the “Micro-radio” programme, a little girl fled the microphone, Roos and Plouffe made final adjustments to the evening’s sound collage, and then we were led through a hagiography of Saint-Roch, the patron saint of dogs and lepers. Astonishingly, no mention was made of the names of the speakers, either the names of the artists, or the historian or the parish priest involved. The anonymity in the work was jarring, accustomed as we are to titles, signatures and the names of sponsors.

The “Micro-radio” project is distinct in terms of its constant movement, which is determined by the context in which it is developed (in this case, Saint-Roch). For the broadcast, Roos had brought a laptop, a console, a low-power radio transmitter and an antenna that he had positioned on the roof of the building, forming a temporary structure. The creative process took precedence over the end result, and this is also a characteristic of the work of Daniel Jolliffe.

As in the work of Roos, movement and sound played central roles in Jolliffe’s project. In addition, he placed an emphasis on listening to others, enabling the audience to become participants in the art work. However, the methods that he used differed. In “One Free Minute”, Jolliffe made an open invitation to leave a message on his voice-mail. The instructions were simple: the one-minute messages had to be unrestricted, improvised and anonymous. He neither modified nor censored any of the recordings, with the exception of incitements to hatred, which are illegal in Canada.

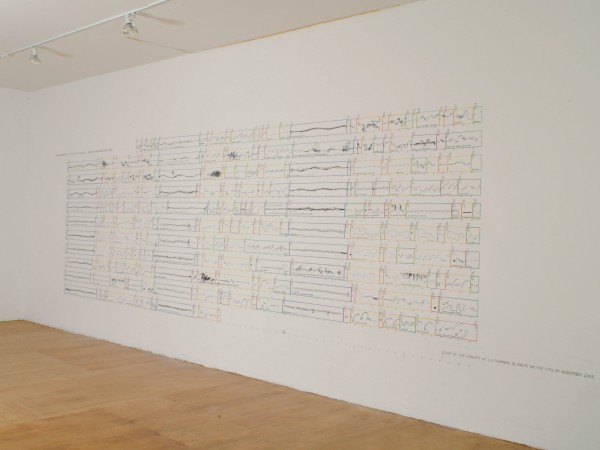

The artistic experiences that Jolliffe subsequently offered the public are a testament to his interest in interactivity. He created mechanisms of participation that demonstrate how technology can affect our perception of space and our means of communicating. As for the project One Free Minute, it offered an “on-line” interactive environment by means of the telephone and internet. Each evening from the 9th to the 15th of June, he engaged with the public space of the exterior agora at the Gabrielle-Roy library. As soon as the building closed its doors, the artist parked his bicycle, which was equipped with a broadcasting system, consisting of: a large sound amplifier fixed to a conical casing, of a yellow similar to that of the background colour of warning signs on roads. The shape of the fibre-glass sound amplifier resembled the ear trumpets on early gramophones. The entire structure was connected to a mobile phone and a small MP3 player. And so, in the centre of the square, as well as neighbouring roads, we heard the messages recorded on his voice-mail.

This action was not dissimilar to Martin Dufrasne’s performance at the “Émergence” event at the Ilot Fleurie in 2002. In this performance Dufrasne gathered the complaints of passersby and then broadcast them in the city centre using a megaphone. However, Jolliffe’s work did not focus on the recriminations of the population, and he avoided the populist bent that the work could have taken, and which is common in the media. Instead we heard a diverse group of messages and sounds, ranging from publicity for the next Reclaim The Streets event, to a wood crafter’s saw, by way of sung messages, language courses, philosophy quotes, and a classic – but touching – minute’s silence. Given that it is not customary to hear strangers express themselves publicly, and without restrictions, the effect of the messages, as a whole, was, “at the end of the line”, extraordinary. Naturally, such a hubbub left no-one indifferent, with many approaching in curiosity. Adolescents reacted to the singing coming from the device. As the messages were spread by the sculpture on wheels, the artist handed out business cards inviting people to dial his number or visit his site. Some found the whole thing hilarious, others were disturbed: a policeman did not appreciate an anonymous person sending him packing in a recorded message; a regular visit to the area would have preferred to have taken his dose in peace, without all the uproar. An apostle of “good old common sense” rattled his brains trying to understand the relevance of the soundtrack: “Why reappropriate a public space, which by definition already belongs to us? Why give a platform to people indiscriminately? Shouldn’t this be offered to a select group rather than to the rabble of the downtown area?” And this rabble responded: “Why do the authorities tolerate this thing howling, but force me to turn down the volume on my sound system?” Aesthetic problems aside, the work caused much discussion and brought up questions of a legal and ethical nature.

Technology changes the way that we communicate, and by virtue of this it transforms the way that we learn. Nowadays, essays can be accessed on the Internet, amongst them, one by Hakim Bey, on the concept of the Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ), which sheds light on the works of Kristen Roos and Daniel Jolliffe. Bey considers that all forms of revolution are also traps, because they rapidly become simulations of themselves. However, in order to counter the numbing of consciousness in an “era in which the speed and fetishism of merchandise has created a false and tyrannical sense of unity, that tends to obscure all forms of individuality and cultural diversity”1 he suggests that there exist Temporary Autonomous Zones, or zones of nomad activity whose mobility and temporality enable people to avoid normalisation and reification. These anti-conformist somersaults are presented as a form of tactical uprising, aimed at thwarting the “the mega-entrepreneurial information State, the empire of spectacle of of simulation.”2

In terms of their unconventional and event-based character, the works of Roos and Jolliffe echo Hakim Bey’s TAZ. Bey remarks that: “We have noted that the TAZ, because it is temporary, must necessarily lack some of the advantages of a freedom which experiences duration and a more-or-less fixed locale. But the Web can provide a kind of substitute for some of this duration and locale–it can inform the TAZ, from its inception, with vast amounts of compacted time and space.”3 is precisely the role played by Roos’s and Jolliffe’s Internet sites. According to Bey, the greatest strength of TAZ lies in its invisibility, and that is why “as soon as the TAZ is named (represented, mediated), it must vanish, it will vanish.”4 As to whether TAZs can take an artistic form, it seems that it is certainly the case with the “Micro-radio” and “One Free Minute” projects. Bey writes: “Here I wish to suggest that the TAZ is in some sense a tactic of disappearance. The disappearance of the artist IS the suppression and realization of art, in Situationist terms.”5

By giving a platform to the people of Québec, by proposing mobile forms and discourses in motion, and by disseminating these anonymously, and at the limits of the law, the artists Kristen Roos and Daniel Jolliffe truly turned the Saint-Roch area into a temporary autonomous audio zone. In terms of the theme of ‘The Transmission of Knowledge’, let’s leave the last word to Bey: “The key is not the brand or level of tech involved, but the openness and horizontality of the structure.”6

- Bey, Hakim. 2011, T.A.Z: temporary autonomous zone. Translated from English by Christine Tréguier, Paris: De l’Eclat editions. p. 24.

- Ibid., p. 13.

- Ibid., p. 28-29.

- Ibid., p. 14.

- Ibid., p. 62 et p.67.

- Ibid., p. 29.

Hélène Matte