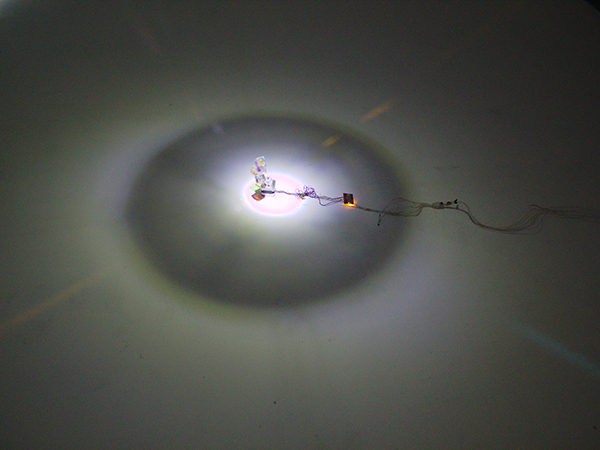

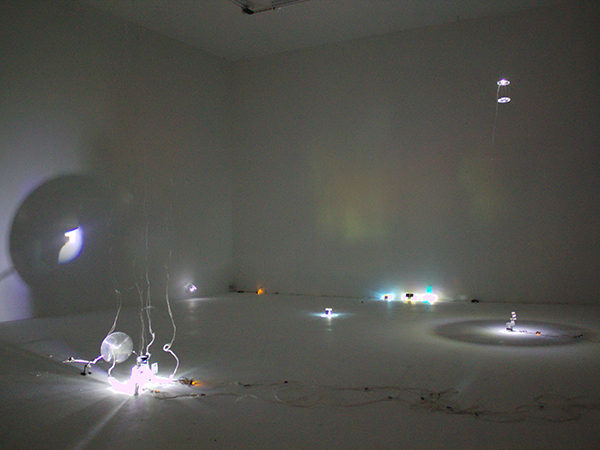

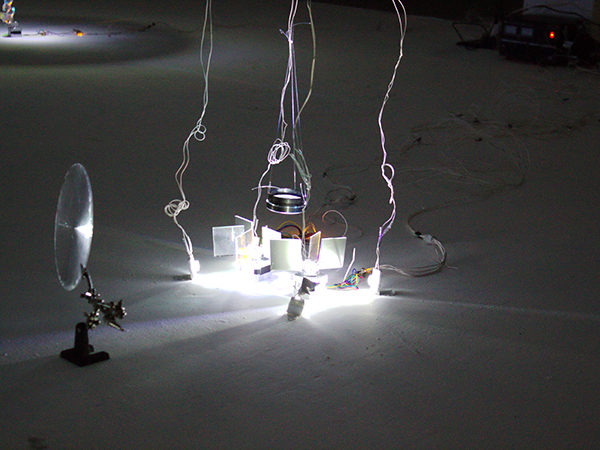

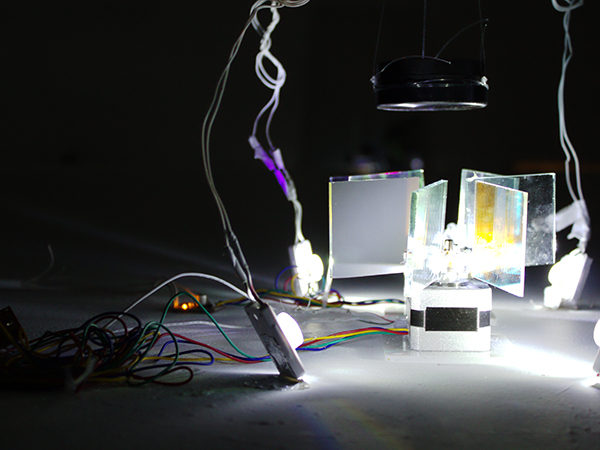

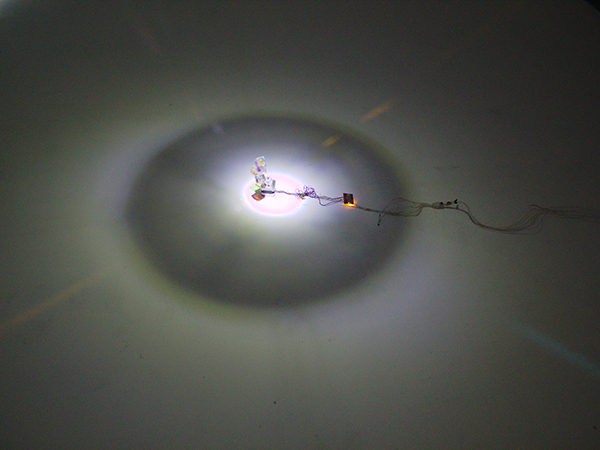

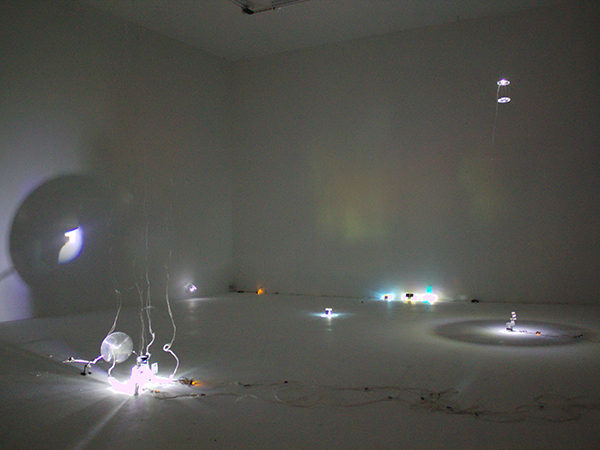

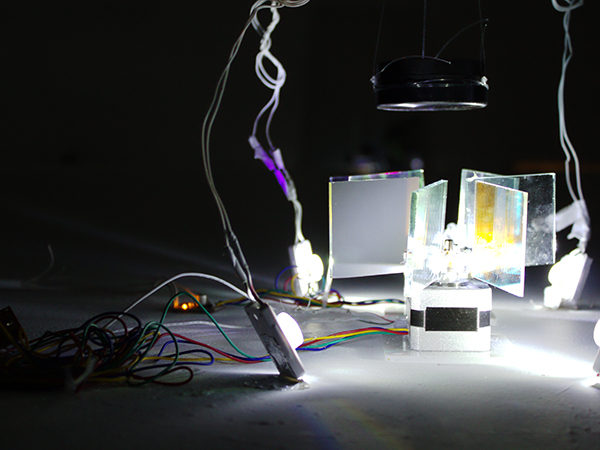

In LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE gallery, multiple light sources are paired with compositions of glass and dichroic prisms, mirrors and photographic lenses. Some items are stowed to randomly set engines in an unpredictable movement, at once relentless and delicate, to deploy light in a changing iridescence, accompanied by the sound of the engines and the clatter of the materials at work. Immersed in semidarkness, the gallery lights up with this series of installations projecting onto all surfaces of the space a polychromatic radiance that roams the room without invading it and continually redraws its contours, just as they react to the configuration of the space.

crédit photo: Carol-Ann Belzil-Normand

Alice Jarry and Vincent Evrard thus put the constitution material of the cinematographic image at the service of a diffractive game on several levels, composing this iridescent constellation significantly named Lighthouses. The phenomenon of light diffraction is here convened at the forefront. Even more, the logic of the diffraction, as a mode of interpretation and interaction with reality, permeates the entire work. Light itself is thus integrated to a dynamic of physical and semantic interactions suggested by its wavelike properties. It does not serve to show a picture or an object to be revealed: but rather, each of these small beacons is a source of light and sound deployments each occurring through others, dealing and interfering from the onset with all the components of the environment, and plunging the participant at the heart of its modulations.

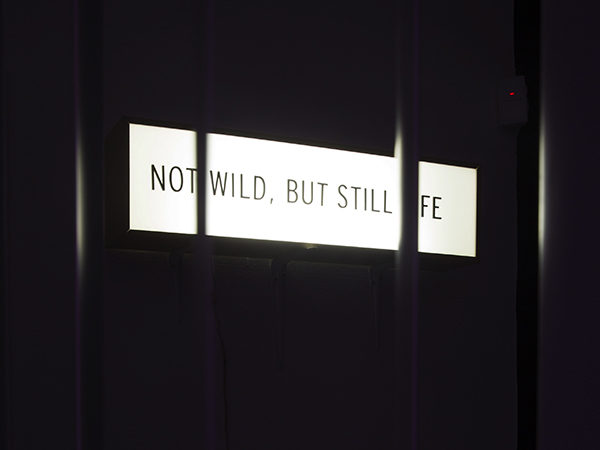

Diffractions

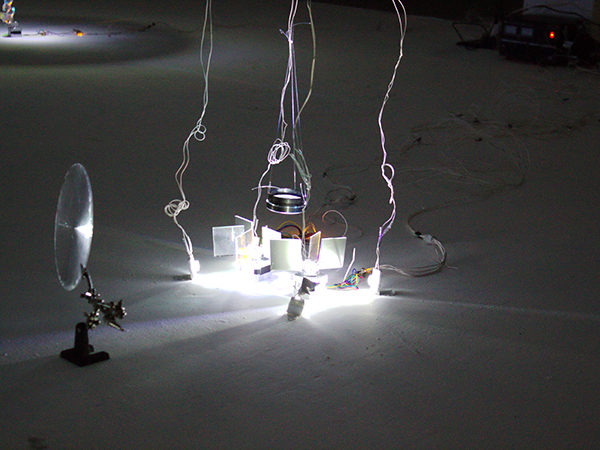

Diffraction is the optical phenomenon in which light rays are deflected and disseminated when meeting the edges of an obstacle, which allows to separate the light into distinct beams of colour and recompose them in white light. Current image projection technologies operate the diffractive properties of the lenses and dichroic prisms, jointly with assemblies of mirrors and lenses. These components are here repeated at new expenses, to be assembled in an unusual, open and dynamic fashion. The installation thus presents itself as a series of deconstructed but functional small projectors, each piece operating according to its own logic in a new and unpredictable composition.

crédit photo: Carol-Ann Belzil-Normand

The diffraction process is thus at the centre of an installation that strips the light of its representative, or mimetic function to let it act in its own materiality, into the very components that daily lead it to our screens. In addition, the installation is not confined to the juxtaposition of a series of small lights spread out in the space. The whole is cohesive, not only according to a specific orchestration, but because the bright deployments circulating in space and the sounds produced by the installations intersect and interfere. Ultimately, the actual encounter of the artists can be understood in these terms: light entering in LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE through the intervention of Jarry and Evrard appears in points of meeting resulting from the interaction of their approaches.

A meeting, notably of a sensitivity toward the singularity and the power of action of the matter, and attention to the constitution process of the meaning and the narrative.

crédit photo: Carol-Ann Belzil-Normand

This approach is part of the method of diffractive reading developed over the past two decades, particularly by Donna Haraway and Karen Barad. While the optical phenomenon of reflection structures the classic paradigm of knowledge, according to which the truth of representation depends on its resemblance to the original, the diffractive approach lets us learn how to think following the logic of the deviation and the diffusion of light waves.

Indeed, these produce illustrative interferences, such as the objects encountered as well as movements of light itself. To the discourse on materiality, the diffractive reading prefers the entanglement of the materiality and the discourse. To the knowledge understood as the adequate reflection of objects kept at a distance, it prefers knowledge experienced as a concrete practice of commitment in the world. It seeks to account for the significant meeting points between the materiality of things and the sense with which they are invested1.

The Reality of the Image

In this frame of mind, the film screening materials are here put in action in a way that dissolves the usual frontal quality of the image. This image is a statement of a reflective logic: the image must be a mirror of the original; either the most perfect representation of an idea, the faithful imitation of a reality, or at least some of the traits of said reality for the benefit of the success of an illusion. Thus, ultimately and perhaps paradoxically, the successful illusion– therefore the image resembling reality- tends to dissolve the identity of the viewer. This one, absorbed by the visual and sound show deployed in front of him, loses and forgets himself in it. That is not the only thing of course, but it must be clear that the omnipotence of contemporary film and video are of this order: they catalyze the viewer’s renunciation of his commitment in reality. Thus, the image is used to not see, to not take a stand.

Here, rather, the spectator necessarily becomes a participant in meeting with the materials that constitute the image itself. The staged light does not intervene as a neutral agent erasing itself in the revelation of the objects rendered visible. On the contrary, it reveals itself, shows itself at the same time as the bodies that it enlightens, and which in turn modulate the trajectories. The shadows, on the other hand, do not embody the simple negativity of the absence of the visible. The body as an obstacle acts not only to stop the light, which draws the negative silhouette of the obscured object encountered, but also by diffraction, as a sign of its wavelike and polychromatic properties. Similarly, the rattling and shocks underline the materiality of the image often associated with a kind of immateriality of the light. The light itself, beyond its ethereal nature, thus appears in the work of a materiality which acts upon the bodies that show themselves by reflecting it, absorbing it, by blocking it, etc. In addition, the technical devices implemented are visible. As much as the movements of the participants, the intervention of the artists is apparent: wire and engines are part of the whole. Present in these traces, they withdraw yet at the last moment to let chance decide the movements of the engines.

Crédit photo: Pierre-Luc Lapointe

The play of the projections thus deployed does not favour the dissolution of the viewer in the image. In this dynamic where light, materials, shadows and people are moving together, no posture allows the participant to ignore its position. It is always immediately and visibly active. The passivity of the viewer that is assigned to a position of receptivity is undone to push him into the co-constitution of forms deployed in space. Indeed, it is impossible to access the installation without affecting it. Necessarily, the light beams meet the body of the participants, whose shadows interfere between the shapes projected on the walls. Similarly, the sound of their steps, the sound of their breaths, and even their words meet the rattling glass ringing in the space. The viewer becomes a participant while he meets the materiality of the cinematic image in a way that forces him to reinterpret and recompose his rapport to it, to respond to the movements in which the image works itself around and through him.

The Little Light

As he takes part in the installation through his body and gestures, the participant also enters inwardness areas. The installation, by the separation of the light and the effects of chiaroscuro, creates an intimate and reassuring space bringing him back to himself at the same time as it directs him in space. Here the show’s externality and the inwardness of the consciousness are crossing. The effect is not unlike the pages of Gaston Bachelard on what he called the musings of the little light. These are foremost, for the author, inspired by the flame of a candle, flickering fragment of fire, carrying the observer in the familiarity of a quiet reverie: “In all, the chiaroscuro of the psyche is daydreaming, a quiet, soothing reverie, which is faithful to its centre, lit in its centre, and not tightened around its content, but always somewhat overflowing, filtering its light into its dusk.”2 The installations are reminiscent of such a description: light sources spread around themselves their soft iridescence, exercising a kind of force of attraction and fascination.

crédit photo: Pierre-Luc Lapointe

To Bachelard, in fact, the electrification of the lighting has resulted in the loss of this intimacy with the light once provided by the candle. Yet, here the bemoaned effect of the flame flickering in the night of a pre-industrial time is now met through technology itself. Material vectors of the flight into the image thus bring the participant back from the distant to the close, from the externality of a represented world to the proximity of an inhabited world—or one to be inhabited.

Horizons…

If the Lighthouses of Jarry and Evrard guide us, it is not in a way to indicate a destination. This technological constellation shifting and deployed in the same space we roam does not offer a stable and distant landmark dictating the direction to take. It rather accompanies us in our movements in a way that etches them at all times in the materiality of the visible: at all times our place is shown to us in the changing configuration of the space. Lighthouses thereby makes us meet the traces of our participation in the reality of the cinematographic image, precisely at the point where we have the habit of forgetting ourselves. Through these paths there is a consolidating experience revealing that the cinematographic illusion is not in the projected image, but in the separation of the passive viewer who would remain a neutral observer.

- Barad, Karen. 2007, Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham and London : Duke University Press, p. 86 et suiv.

- Bachelard, Gaston. 1961, La Flamme d’une chandelle. Paris : Les Presses Universitaires de France, p. 17.

Dominique Lepage