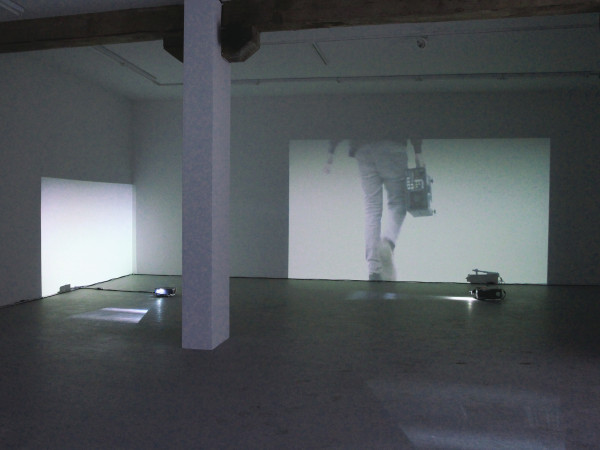

On the occasion of her residency at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, the Brazilian artist Karina Montenegro exhibited the results of her two months of in situ work. This project was made possible through an exchange program between the Museum of Image and Sound of São Paulo in Brazil and LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, Avatar and La Bande Video in Quebec City. These few weeks spent faraway from her country and her familiar reference points enabled the artist to leave a trace of this in her artwork. In the installation titled Deslocamento – O Jardim de minha casa, translated literally as “Displacement – The Garden at My House,” the artist proposes a poetic view of her move to an unknown place, inspired by her personal and professional experience.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

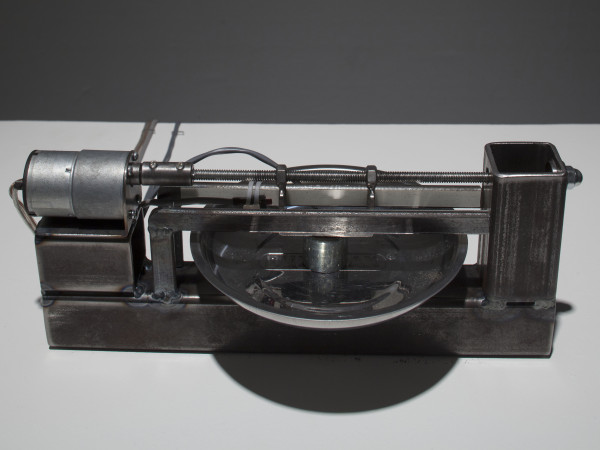

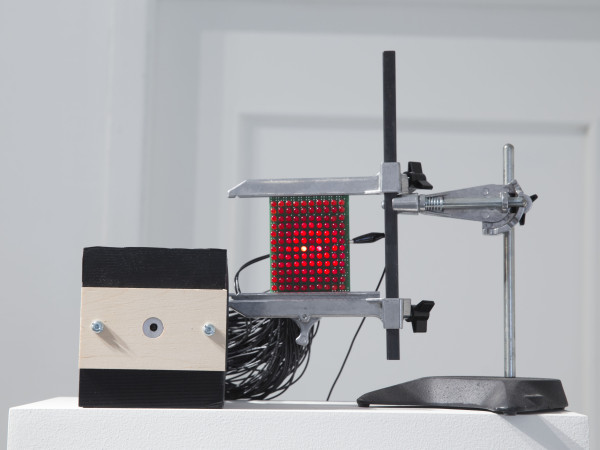

This work fits in perfectly with the artist’s way of working, as she is interested in the links between art and technology and new medias. This artist, who is both a programmer and researcher in art, design and audiovisual and digital medias, uses these complementary competences, stemming from her studies in science and in arts, to show the intersection of art and the digital.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Her interest in the influence of new technologies on our perception of time and space is moreover very current. Considering the constant progress of our means of communication, Karina Montenegro is asking questions about the vast possibilities of these contemporary communication techniques. According to the artist, contemporary society is deeply affected by the various means of communication and the constantly evolving technologies, which influence the way we perceive the world. She believes that the development of most communication techniques come from a basic human need to preserve history and memory.

She maintains that technology opens new perspectives and gives us numerous possibilities concerning time and space. Today, as a result of technology, one can be “elsewhere” without having to move and can have access to information from other times and from everywhere in the world with just one click.

The artist’s gaze is also critical about technological progress, because, according to her, this has made communication much more complex today. The speed with which the technologies are developing makes them difficult for the general public to assimilate. 1

The Work

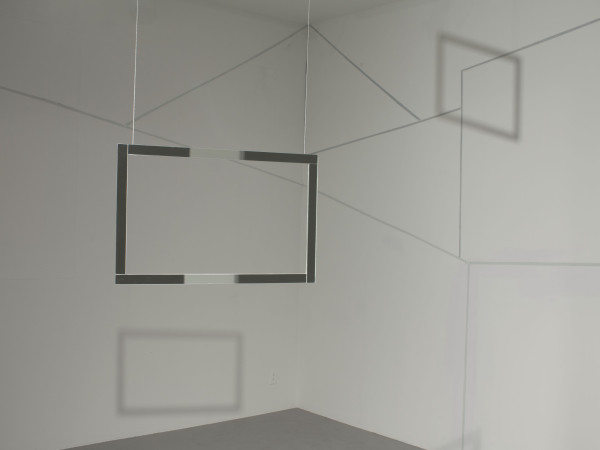

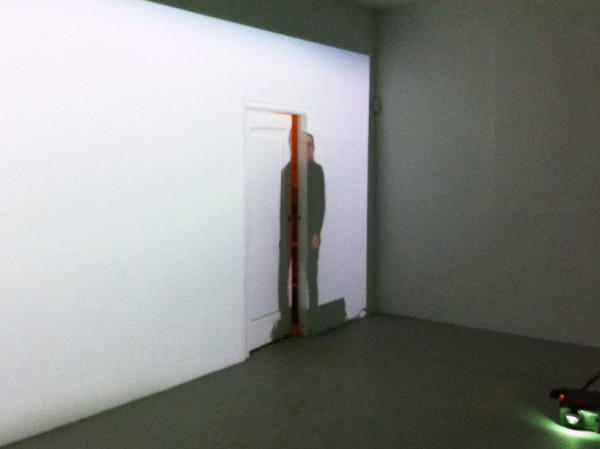

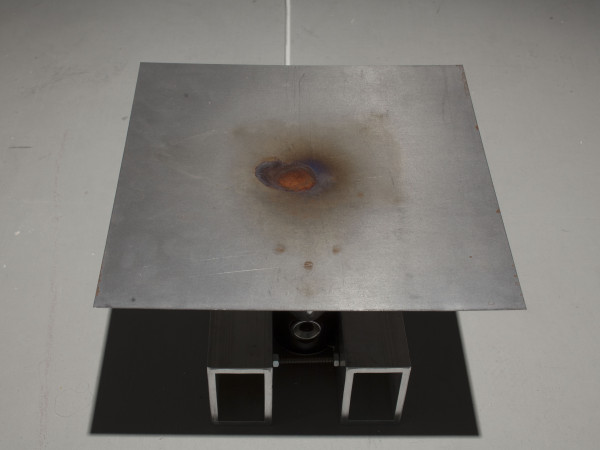

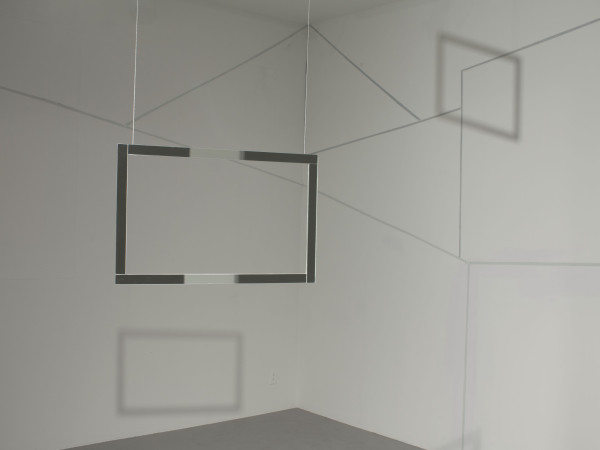

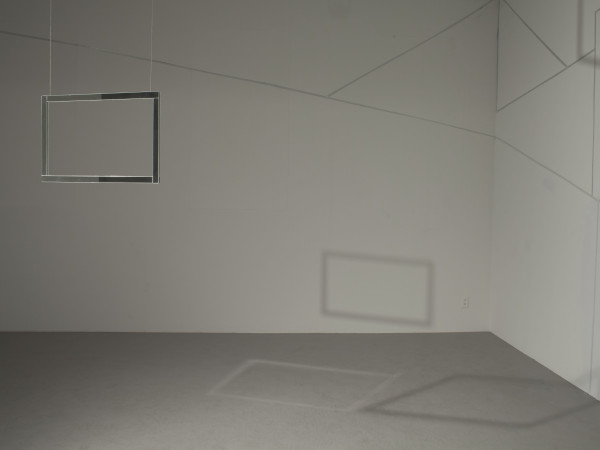

Right in the centre of the gallery, a shimmering frame is suspended and spontaneously attracts the visitor’s attention. Put into motion by a timer, it turns in the opposite direction to the hands of a clock, carrying out one movement per second. It takes 360 seconds for it to make a complete tour of the space. This minimalist installation is perfectly integrated into this part of the main gallery (see photograph).

The presence of the frame with a completely empty space surrounding it is a little intimidating at first. Visitors need to take a moment to become familiar with the work and to find their way in this strange unoccupied, empty space.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

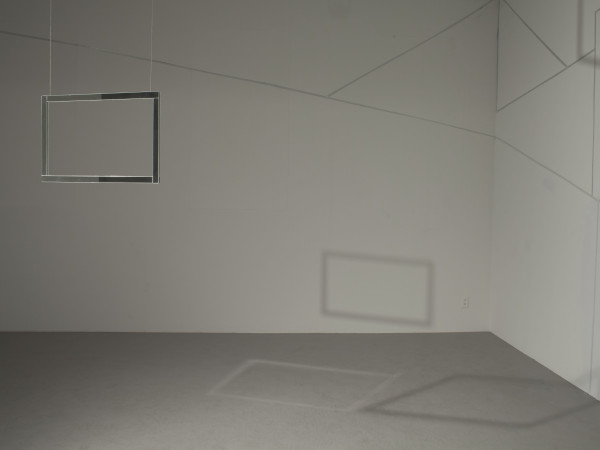

The immense geometric forms are not much easier to understand. They circulate slowly, moving alternately on the four gallery walls and the floor. They are generated by the reflection of the lighting elements on the shimmering frame. These clear trapezoidal forms turn at a frequency two times faster than the frame, which makes the visitors feel destabilized. The numerous shadows of the frame are fixed however, but turn at the same rhythm as the frame. The reflections and the shadows of the frame confront each other in the space, creating confusion and an interesting trompe l’œil effect.

A few gray lines placed on the walls create a geometric motif, breaking the monotony that monochrome walls usually have. For the artist, these geometric forms refer symbolically to her distant house and garden, her displacement.

The empty frame in the work is proposed as an abstraction of the window of her house in São Paulo. These two elements go beyond the simple representation of a home. They refer more broadly to the multiple ways of perceiving time and space. The work is not located in a precise time or space. Instead it evokes an abstract, dislocated time, a different time, another possibility of time.

The artist borrows the notion of heterotopia from philosopher Michel Foucault to present us with incompatible spaces and places that are juxtaposed.2 Michel Foucault defines heterotopias as a physical localisation of utopia. In other words, they are actual spaces where the imagination exists.3 These are places of alter-reality, that are neither here nor there, that are simultaneously physical and mental. These places are entirely different from all the places that they reflect. Foucault uses the idea of the mirror as a metaphor for the duality and contradiction, the existence and non-reality of utopian projects. A mirror is a metaphor for utopia, because the image that you see there is not real, but is also a heterotopia because it is a real object that projects the manner in which we are connected to our own image.

“The mirror is, after all, a utopia, since it is a placeless place. In the mirror, I see myself there where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space that opens up behind the surface; I am over there, there where I am not, a kind of shadow that gives my own visibility to myself, that enables me to see myself there where I am absent: such is the utopia of the mirror. But it is also a heterotopia in so far as the mirror does exist in reality, where it exerts a sort of counteraction on the position that I occupy. From the standpoint of the mirror I discover my absence from the place where I am since I see myself over there.” 4

It is for these reasons that the frame, the work’s central component, is made of mirrors. For the artist, the shimmering frame represents the way that she perceives the world with its shadows and reflections. It is a metaphor of a flat world, in the sense that there is always the possibility of seeing beyond what one perceives. The mirror is linked to the representation of ourselves, the illusion of who we are.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

For Karina Montenegro, these utopias of time and space exist and are found within us. It is sufficient to look at things differently, to change one’s viewpoint to find them. The artist took advantage of her trip to Quebec and her stay away from her country of origin to change her point of view and her rhythm of life and to get closer to, as she calls it, the suspended time that she was seeking.

Deslocamento enables visitors to have both a spatial and visual experience, all while being a response to the artist’s existential questions. The work makes visitors confront their perception and their relationship with the space, both that which surrounds them and that which they inhabit. These two spaces, internal and external, real and imaginary, mental and physical, overlap each other.

Deslocamento – O Jardim de minha casa is the first stage of a project that will be continued in Brazil. The artist is thinking about recreating the installation with the same structure in São Paulo. The work then will become the abstract representation of Quebec City in Brazil and symbolically complete the artist’s movement.

- Information from the artist in conversation with the author, November 12, 2012.

- Foucault, Michel. 1984, “Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias.” In Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité, No. 5, p. 46-49. Website [online]: http://foucault.info/documents/heterotopia/foucault.heterotopia.en.html (consulted on November 2, 2012).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Katarzyna Basta