“Shit! This armchair at the entrance to the studio disturbs me!”

In today’s contemporary art world, Paolo Angelosanto’s work is a genuine encounter between individual and social realities. For several years, his research has been centred on a radical analysis of himself. This process, inherent in his work, is in tune with the outside world.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

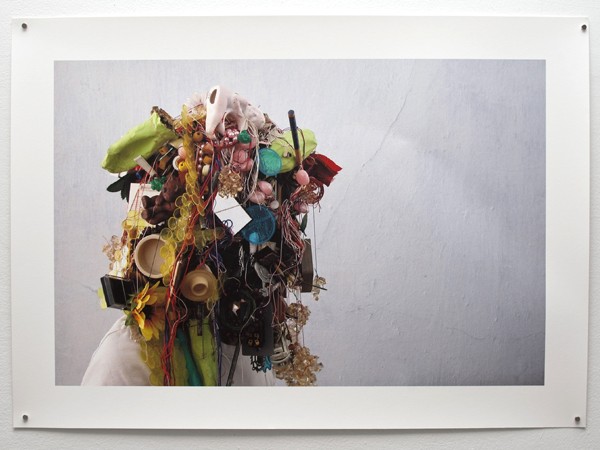

A protagonist in performances that he calls “movements of painting,” Angelosanto plays, divides in two, changes, manipulates and restructures various scenographic proposals, becoming the subject of the represented events.

His interventions concern photography, performance, drawing, painting, interactive sculpture, photocopying, video and other mixed disciplines.

Looking retrospectively at both his present and past memories, Angelosanto draws a chart, a kind of contemporary postcard. In the performance Welcome (June 2001), for example, during the inauguration of the 49th Venice Biennale, the artist set himself up among the visitors with a machine to produce cotton candy. The idea was to make a gift to the public of a biodegradable sculpture, a kind edible energy before they faced the long trip through the biennale. A welcoming gesture in which the viewer, by the mere fact of arriving, entering and observing, would thus create a work using his or her childhood memories.

Some of Angelosanto other works are directed at contemporary globalisation’s sensitive spot: incommunicability. There is the video the artist made during his sojourn at UNIDEE Citadellarte-Fondazione Pistoletto in Biella (Italy) in 2003: Ten words for Love Difference. Ten artists at the residency were invited to recite ten words in the language of the host country in front of a camera. Likewise, in M’ama non m’ama (Love me, Love me not), in which several people of different nationalities close to the artist play she-loves, she-loves-me-not to the rhythm of the cantilena.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

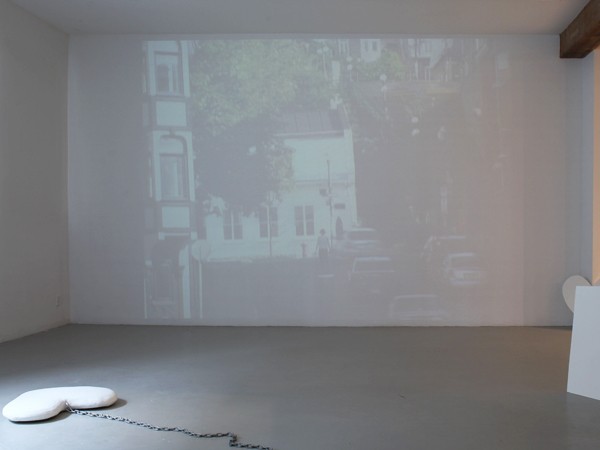

While historically the artist’s profession has been a rather solitary one in which the artwork was transported from the studio to the exhibition space, and only then did it receive acknowledgement, which according to many, contributed to the work’s completion, for Paolo Angelosanto, this process is a transit between the studio and the museum and a form of reflection on the subjectivities confronted in this context. In accordance with these criteria, Angelosanto conceived of Interno 12 in 2004, offering a number of artists a place to elaborate a collective project, motivating them to produce a work. For one day a month, they would make the role of the protagonist public at an exhibition-encounter in a private space.

“I was carrying out work centred on my own image. I needed to exchange with other artists. I believe that art doesn’t have meaning unless it is seen, unless it has a social aspect or that the public can identify with it. I am not a gallery director, curator or critic, I only was thinking of work that would make me open up and communicate with others. My studio was twelve square metres, I looked for twelve artist from studios and collectives, I gave myself twelve months of work and there were twelve encounters with the public.”

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

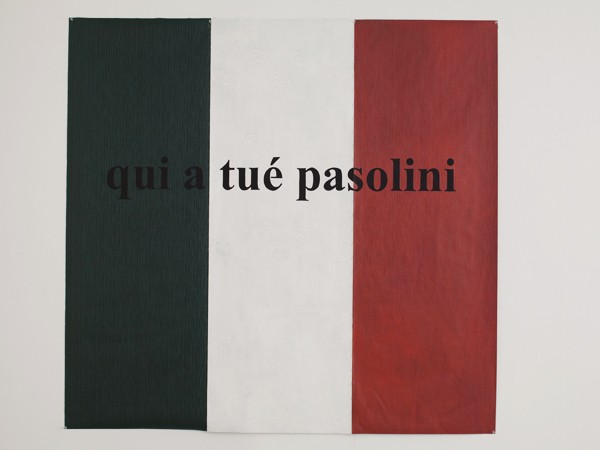

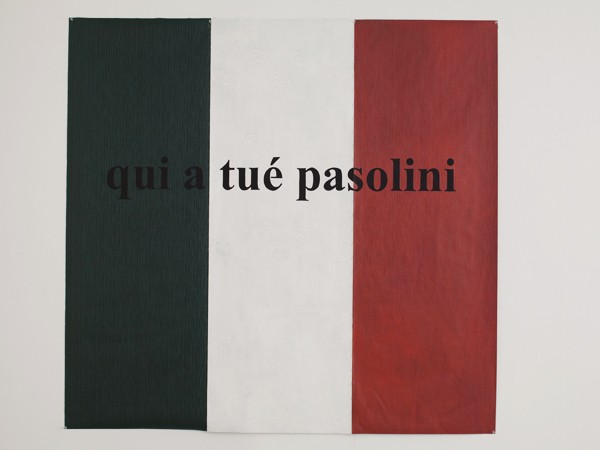

This is not new in Angelosanto’s career. There was another in situ work presented in Canada titled Je me souviens. The project consisted in a performance presented in the Saint Roch neighbourhood of Quebec City. Exhibited there were a cement sculpture, two mural works and a video of a trumpeter player dressed in a uniform of the Louis XV era. This event was part of the residency that the artist had at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE in Quebec City in August 2010. The forms used and resulting from the cut out of a cement heart were converted into sculptural elements making up an exhibition in the gallery. This also included two paper murals of 150cm x 150cm. They both represented the flag of Italy, having on one, the text Je me souviens and on the other Qui a tué Pasolini (I remember and Who killed Pasolini). The local population was invited to meditate or to say the first word that comes to mind when one thinks of Italy.

“If all object is, in a some way, immanent to the cognitive subject, inevitable limit of knowledge at the same time as the unique possibility of knowing, what to say about language?” wrote Octavio Paz. “The boundaries between object and subject seem blurred. The word is man himself. We are made of words. They are our unique reality or at least, the unique testimony of our reality.”

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Words thus are transformed into symbols of differences between peoples and cultures, between experiences and representations of the world.

“My main objective is to develop new ideas and evolve as an artist, continuing my research both in the field of performance and in the visual arts. I believe it is possible to make public interventions, using various forms of communication.”

In his project, Je me souviens, Angelosanto tried to establish a relationship, a meeting point, a link between an aspect of his identity as an Italian artist who finds himself in an unfamiliar country and the work that he produced in Italy before leaving. Je me souviens contains all that he needed to elaborate his thoughts and concepts that have arisen since the first day of his residency in Canada.

“But on leaving Italy, one realizes that no matter where one goes, one carries everything within.” Memory, love, solitude, nostalgia for one’s home, for one’s country, the beauty of one’s cultural heritage: “Through this experience, I would like to be able to make a connection between my art and the place, establish relationships with the milieu, and create a synergetic collaboration here with critics, artists, organisations and institutions.”

Thus Angelosanto’s artistic production is an amazing interpretation of the intermediary spaces between things, colours and objects. He refuses the general description: the narration of a story is of secondary importance in his work.

The exhibition turned out to be a choreography of forms. A series of projects, ideas and concepts carried out in full at the last stage, acquiring a new presence.

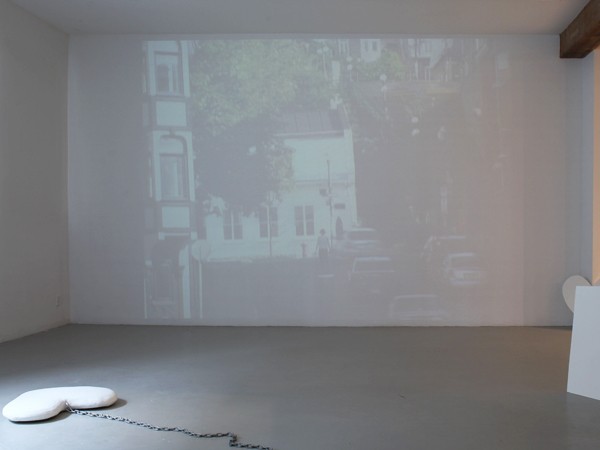

The cut out of a heart leans against a wall: this is the heart that was pulled around in the streets of Quebec City. The form of this heart was modelled in cement, presenting the weight of this heart, the fragility of this love. Thus the wall sculpture became merged with painting. The artist, who exposed his body to bad weather, dragging this weight, attained a sculptural body language and expanded the work’s narrative. These works are distinguished from the two-dimensional nature of his work on the paper mural. The project concluded with another performance, a work stemming from the other: Je me souviens ends with Angelosanto sitting on a strange armchair, where he weaves a flag, intertwining the colours red, white and green. These colours give a maximum, meaningful tension to the gestures of the hands, producing mental landscapes that we carry along towards a romantic fantasizing. The work is a materialisation of ephemeral poetry, flesh and spirituality, fertile ground conducive to illusion.

In Italy, one calls Garibaldinos those who embark on a business without having infrastructures. Leaving Italy and bound for Canada, Paolo Angelosanto had wanted to represent someone having this type of character. The idea came from the need to play a character who could represent Italy, who as well would be know in North America, and who would coincide with his way of being or who would be able to establish a reference to his way of working. “I think regularly of my way of acting and proceeding,” he says, “I’m an artist who will do the impossible in order to produce my work.”

He arrived in Canada and looked for ideas and inspiration. He found himself in Parc de l’Amèrique Latine dedicated to Simon Bolivar, where there are numerous statues and flags in tribute to the liberation of the Americas. In this square, there were two pedestals without sculptures. He took over the place for a day with the intention of transforming it, in situ, into a genuine living monument, putting into play his own “I” to convert it ultimately into his alter ego, as part of a new social and cultural subjectivity, rebelling against language. He went out looking, searching until he found a place that had nothing to do with his concept of place, a virgin site set up with monuments and statues in which flags waved. But in his Italian way of seeing things, this place had nothing to do with a site that is commonly used to welcome people rather than aesthetic symbols. He succeeded then in reformulating a hypothesis, a process, a vision of the world and for this he “mimicked” himself. He added himself to where there were only the pedestals, placing himself in the foreground where there was an empty spot, where something was missing as a result of restoration or theft. It is a predicate without subject because he poses as a Garibaldino who is superposed on the issue of this solitude, from this perspective, in a site in Quebec City, thousands of kilometres from his city (Cassino? Roma?). Similar to Garibaldi in Montevideo one hundred and fifty years ago, saying to the world that there is a place without place that is nowhere and everywhere, because contemporaneity has been able to reformulate this start and this end as well, which is a new beginning, the concept of “here,” where everyone finds his or her origins.

“Precisely because the work of art and the adventure are confronted in life, they are the one and the other similar to the whole of life itself, such as it is presented in the short encyclopaedia and the condensed existence of dreams.”1

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

This is the artist’s real and imaginary trip across the city and at the same time, an invitation to be confronted with social contradictions: a way of revealing the codes that efface meanings, accentuating the destabilizing effect.

I will chance a last thought: in his work, Angelosanto goes beyond the boundary between personal and collective space, reconfiguring a reality that in contemporary art appears definitely organized, thus inverting the nature of this quest for his own language. So his challenge is transformed into a defiance of art. As well, I say that the fact of going and producing cotton candy at the Venice Biennale is a gentle and perfect provocation. This has to do with love, in the most profound sense of the word.

- Heidegger, Martin. 2014, De l’origine de l’œuvre d’art. Paris: Rivage editions, 120 p.

Antonio Arévalo