A continuous flow

par Coline Ellouz

Robbin Deyo

from April 20 to May 31, 2009

“The deepest thing about man is his skin.”1

Enter and follow. Choose an anchoring point, knowing that it will be lost. Circle, from one wall to another, following an irregular line, somewhere between a curve and a straight line. The movement seems to take on the shape of life itself, if we weren’t stopped in our path by a sense of destabilization.

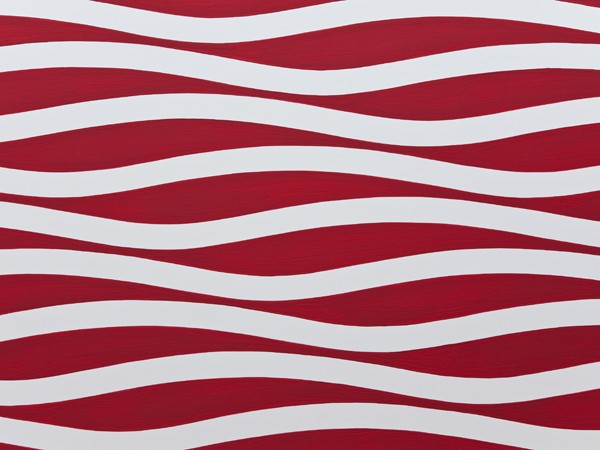

Initially, Robbin Deyo’s installation is experienced on the surface, as a series of lines spread out evenly across the walls of LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, one after another, one over the other, like a pavilion, as Michaux would say. The lines of varying density unfold along the length of the walls, forming an impressive flow that is only broken by ‘breaches’ in the architecture at particular points: a door, a window, a pause for breath.2

And so the line extends outwards, and it is for the eye to reconnect its interrupted movement, for the eye to join one side of the thread to the other. In the center of the space stands a column. This separation in the space, similarly to the walls that surround it, is covered in stripes, horizontal bands running from east to west, as well as undulating lines running from north to south.

And so the eye begins to see beyond the surface, or more precisely within the surface. A loss occurs, causing us to forget the referent ; drifting through the architectural details of the space, the lines appear to be painted (and indeed Robbin hand-painted this system of dual openings). They unfold into their own depth, as though uncovering their own internal structure, rather than covering the walls ; as though during her residency at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE Robbin Deyo had not so much painted as excavated the building, revealing its structure, bringing its strata to the now-exposed surface.

In the landscape of the windows we see a crucible of light. A crucible of matter also, as another dimension is revealed: in the horizontal openings, the motif of the line is broken, making way for long, red-tinted slats. The window has become a cliff-like form, a living, solid surface emerging, like an outcrop; an entranceway, into the building’s strata.

If the term site-specific means to integrate oneself into a given context, say a building and its history, so this work reverses the equation, in taking hold of the architecture as a means of locating the body.

In the work that Robbin Deyo presented at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, the artist took a risk in working on a scale little-explored up to that point. In a previous exhibition by Deyo (Plein Sud, Longueuil, November 2008), there had been a sense of overflow, a sketching of lines. It was as though the art work could no longer be contained by distinct media, frames, moulds ; as though some of the art had slipped out, imperceptibly, and made its way onto the wall. The limits of space demanded that bodies and instruments twist, at least in the process of making the work ; numerous instruments were deployed, including a spirograph, creating forms beyond the limits of the colorful world of childhood. In Robbin Deyo’s hands, this highly-structured game, which invites the sensible application of the rules of symmetry, became a fascinating means for destabilizing space.

Propulsion and pulsion were evident in the work, in both its sudden bursts of movement and its sense of regular motion. These spoke of the heart, of its emotions and its biology, of its repetition and, ordinarily, its regularity of pulsion/pulsation.

Ordinarily regular. The undulations of the lines, whose curves became more pronounced as they climbed upwards, became then finer as they plunged downwards, only to swell and rise again. And so to the possibility of prolonging this movement through the imagination. From here also arose the possibility of rules breaking down; the exception proves the rule, and isn’t t the case that still waters run deep? Something unexpected could happen whereby…

Robbin does not reinvent the use of the spirograph in order to retell the story of childhood, nor is the story of life to be found between her lines. Perhaps here lies the strongest link between her work and the 1960s Op Art movement, born of the desire to re-transcribe the dynamics that structure landscapes rather than portray their literal form. According to Bridget Riley, a key figure in the movement, Op Art reveals forces that are “liberated of all functional and descriptive roles”. Form and color are treated as the ultimate expression of the visual realm, in a mode of painting that re-transcribes form, purged of the gaze, in a space where technique has no bearing. These are works without signatures, or œuvres-paysages to employ a term used by Deleuze to describe an ensemble of structural traits for which the artist merely acts as a medium, or vector.3

As we move along a line and then the wave that follows it, one possible effect of the work is that it causes our gaze to lose its way. There is a sustained sense of destabilization, amidst the successive focal points that we encounter, moving from the line into the space as a whole, from the singular to the common, back and forth. This tension between the part and the whole, the uniqueness of the motif and the ensemble to which it belongs, is a defining characteristic of Robbin Deyo’s work. Further to her consideration of scale, Deyo’s work explores negation, upsetting attempts to identify, or fix the gaze on, a clear referent. The question is: in or out, or how to clearly discern what belongs to the interior and what remains exterior?

This confusion seems to leave no doubt as to the exteriority of the work that we are penetrating. Boundaries could become blurred however, and the space seems to speak of “I” The presence of a dense shade of red is impressed upon us: “Red appears as a color without limits, that speaks of warmth, and acts internally, reflecting a sense of the ardor and agitation of life. It contrasts with the dissipated character of yellow, which spreads out and expends its energy on all fronts. With its energy and intensity, the color red speaks of an immense and irresistible power, that is almost conscious of its own strength. A form of male maturity, essentially turned inwards, with little regard for the exterior, emerges from this ardor and effervescence.”4

The words that Kandinsky uses to describe color escape the field of geometry into the field of coloration. Rather than employing pictorial language, he speaks of energy, maturity, ardor and agitation. Color is a vibration, an organ within the composition, a driving force. The painter enters into an almost organic exploration of the grammar of red: from the red that, “sounds a fanfare, resonating the strong, indignant and irksome tones of the trumpet”5 the red that “burns with regularity”6, charged with a power, “a color that is sure of itself, that resists being covered over”7 and the red that possesses “the vehemence of passion, resonating the middling to deep tones of the cello.”8 Such are Kandinksy’s descriptions of the impact of color on the body.

Whilst I have focused here on Kandinsky’s comments on the relationship between sound and color, this is not the sole means used by the artist to describe the bodiliness of color, though it occupies a central space in her approach. As we enter LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, a space that is normally painted white, we clearly feel a sense of vibration, equivalent to something like the feeling of sound; as we cross the space, our entire body vibrates Amidst the lines that run from east to west, how can we fail to see a musical stave, where the melody rather than being inscribed between the lines, is carried between the north and south walls, producing long undulations in which the eye easily loses itself? Here is a musical score, of the texture of sound, in waves that are both seismic and radiophonic, according to the way that we apprehend space, and that space apprehends us.

- Valéry, Paul. 1966, L’idée fixe ou Deux hommes à la mer. Paris: Gallimard editions, 178 p.

- Michaux, Henri, “Un tout petit cheval”. 1935, in Minotaure, Revue no. 7. Paris, p. 11.

- Müller, Heiner. 1987, La bataille et les autres textes. Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 111 p.

- Kandinsky, Wassily. 2004, Du spirituel dans l’art et dans la peinture en particulier. Paris: Denoël editions, 2004. p. 157-158.

- Ibid., p.160.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. Coline Ellouz