10 000 façons de dire presque la même chose: une enquête sur le documentaire web et le cinéma interactif

par Anne-Sophie Blanchet

Quelic Berga

from September 19 to November 19, 2017

Does the way in which we tell a story influence the way it is perceived? Can the ethnicity, age, gender and language of the receiver also impact their understanding? It is certainly tempting to answer Yes… So then, how to build the story? Where to start? How to determine what is essential and what is superfluous? And how to articulate the narrative so that it is as nuanced as the many possible modes of reception? Would that story preserve its essence or would it be exposed to slippage or even loss of meaning? These are some of the issues raised by the recent research of the Catalan artist Quelic Berga.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Inspired by his approach and the works he produced while in residency at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, I propose dear readers, to tell you the story of my encounter with the artist and, in doing so, to leave you with some food for thoughts. From the outset you know that the following reading will not be totally objective (how could it be anyway?) This narrative will be necessarily tinged by my subjectivity, because words, related events and the mere structure of this text are the reflections of a series of personal choice. It will also be dependent on the limits of the medium through which it is delivered, namely writing. All these factors will necessarily affect your reception and your understanding of the work of Berga, but I hope you will accept knowingly to play the game.

Thus, I will barter the “they” of the scientific texts and objective criticism for the “I” and the “we” of a more informal narrative, that of an interlocutor who speaks to you – personally – hoping that this version of the story captivates your attention and finds an echo within you.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

The Initial Situation

In order to prepare for my interview with Berga, I scoured the Internet and the artist’s website looking for information about his background and his areas of interest. I learned that he’s a doctoral student and that his work focuses essentially on interactive cinema and web documentary. He describes himself as a post-media artist, a teacher, a multimedia developer, but perhaps primarily as a researcher. In his works, he is interested in the way that technologies shape our world and how we perceive it. His works thus present themselves as opportunities to explore and test both the limits and the potential of these technologies.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

The Trigger

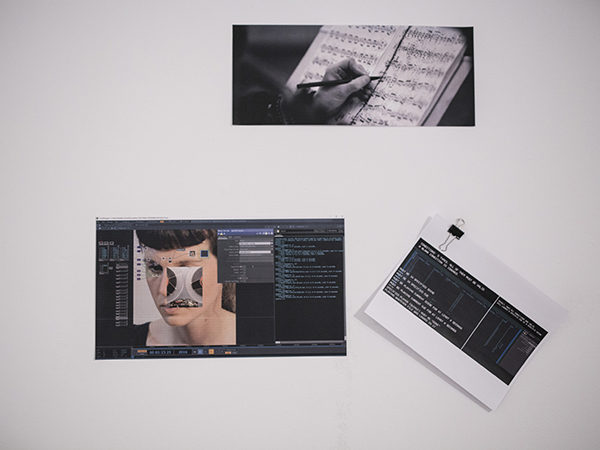

When I walk into the gallery, Berga is already there, sitting behind his computer screen. After the usual presentations, we quickly get to the point. He explains that he has transformed the exhibition room into a research laboratory opened to the public. He has set up several stations, each one dedicated to an issue raised by his works, or to a field of thought about the methodology he must elaborate to carry out his project. In short, it’s a bit like if he opened his notebook and exposed his ideas as they come to him for all to see.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

As a visitor, it is therefore while browsing from one station to another that I can manage to form a general idea. Each element needs to be restored in some order, but the artist – in any case – does not impose a leading thread, and it is deliberately that Berga prompts me to go back and forth in his laboratory. I also understand that I find myself at the heart of a work in progress: the texts, drawings and videos shown are subject to change… some items will be added over the days and weeks while others will be put aside.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

The Crux

Therefore, I find that his work method reflects his comments and vice and versa.

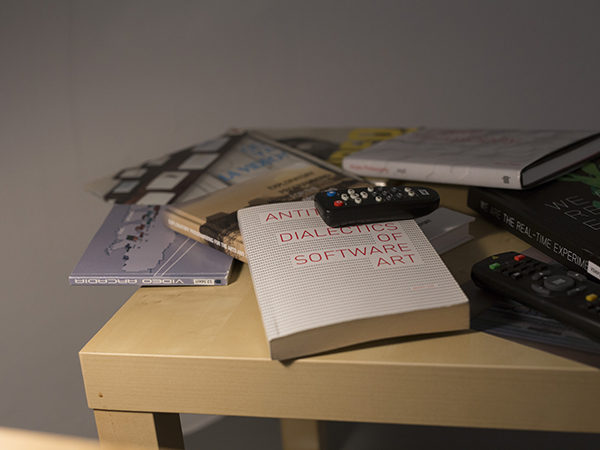

Berga has come to LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE to delve further into the research that ultimately will allow him to design a film editing software. However, this software, rather than imposing a linear editing structure to its users will offer an interface shaped like a rhizome or, in the words of the artist: “a generative form”. In particular, Berga has devoted most of his residency on the development of this new structure. Several options were explored, but the spiral form was eventually chosen to visually translate this fertile concept of the narrative.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

For the artist, in the digital era and with the incessant flow of information, the narrative is no longer built according to a linear sequence, where each event is unique and in direct correlation with those preceding it. The narration revolves in “closed circuit”, that is to say as a loop that would always offer a classic pattern: the initial situation, the trigger, the crux, the outcome and the conclusion. However, with a spiral narrative structure, we get closer to the idea of a loop while allowing the story to follow a trajectory always slightly different. In other words, all the elements of the narrative are present, but they don’t follow one another, they overlap. Therefore, the story becomes a true palimpsest; we can approach it as a whole composed of an accumulation of narratives that each time keeps in itself the variations of the preceding one and welcomes the nuances of the next iteration. In this perspective, the same film could be broken down into an infinite number of versions… like the multiplicity of receptors.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

The Outcome

As the spiral, the image of the cornucopia can help us understand the scope and aims of the project developed by Berga. From the start, the artist aimed to enrich his thought process by meeting the public and other researchers. In this pooling of ideas, some fields of exploration have been abandoned, while others have been further developed. Choices were made that bore new research trajectories that in turn bore other hypotheses and experimentations. However, the Berga editing software will be designed according to the same logic; i.e. as to incorporate the element of chance and external influences (such as the editing interface) that feed and change the trajectory of the creative process. Therefore, the work can be understood as the point of origin of a cornucopia from which the narrative will be able not only to deploy, but also to proliferate whenever it is forwarded to a new receiver via the web.

By developing a generative rather than linear and evolutive editing structure, Berga is inspired by the modes of operation of the Internet and, in doing so, he perfects a language of creation and dissemination that probably expresses better the reality of today. The artist also reveals to his software users the sometimes extremely porous borders that separate their personal choices and those made for them by the machine. Indeed, when a work enters the public domain, a mediation always occurs that could change the way it is received by the viewer. In the case of a web work, a part of this mediation coincides with the time when it is coded for broadcast across the spectrum of the Internet. For Berga, it appears vital to raise awareness regarding the relationships of interdependence we have with technology and the role it plays in the process of creation and dissemination.

The final situation

Technology and possibly digital art have undeniably changed the role of the artist in the creative process. Indeed, when the work arises from the use of technological tools designed by others that the artist himself, his role in the creation cannot be the same as it would in a traditional workshop. This places elsewhere the issue of the author and of what could be called “the aura of the artwork”1.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

With this project, Berga proposes another way of conceiving the timeline of the narrative, outside of the Western paradigm where temporality is expressed in linear form. This changes not only the design of the film, but also its dissemination and the way it is received. Indeed, the use of the editing software that he is developing will eventually be within the reach of any user. Somehow, that will democratize the creative act and will highlight the influence games thrust upon the work from its conception to its broadcast. In doing so, the artist shows interest in the creation/dissemination process where roles are shared and where the notion of the author (personal and unique expression) is not necessarily a fundamental question. The idea is rather to use this artistic research as a tool of critical reflection on today’s world, and perhaps even more so on the modes of production and art mediation in the age of the digital and network creation.

- Benjamin, Walter. [1939] 2008 : The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. Cambridge : Havard University Press, 448 p.