“I’ll never look into your eyes again”

– The Doors, This is the End.

In 2010, John Cornu was awarded the Prix Découverte des Amis du Palais de Tokyo and was given an exhibition in one of the modules of this same institution. Born in France in 1976, he seems not to show any partiality for one medium in particular. Declaring himself “on the look out for cultural techniques, forms or niches that are open to aesthetic experiences,”1 the artist works just as readily with reinforced concrete––at the moment Melencolia at Cneai de Chatou––as with video, photography, performance, woodworking, neon lights or even and above all creative works in context. Although his practice may seem heterogeneous, the fact remains that his works borrow an ensemble of common guide lines, implying some recurrences such as the strong, at times inextricable, relationship to the presentation site2 (Plan Libre, La function oblique, Wash art); an interest in historical, political and current ecological subjects (Laisse venir, Erratum, Cut up); a predilection for “materiological” games and simulacra that lead us to see beyond the immediately visible, disturbing our perception of the real world (Beauty shots, Sibylline); and most recently, reformulating the idea of romanticism by exploring certain codes of art from the 1960s-1970s (materials, forms, presentation displays, production protocol) and some modernist utopias from the viewpoint of fiction, ruin and destruction (Assis sur l’obstacle, Sonatine ((Mélodie mortelle), Macula).

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

This last focus was moreover what was chosen for his residency at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE in the fall of 2009. Titled Tant que les heures passent, Part II, this project was the second part of a trilogy that began in Lyon in the context of the Biennale d’art contemporain (Attrape-couleurs, France), and concluded in Brussels (Galerie Sébastien Ricou, Belgium).

During the five weeks of work in residence in Quebec City, John Cornu concentrated all his energy on producing two sculptural projects: one of monumental carpentry (Je tuerai la pianiste); and a conceptual production in which the work was delegated to Pierre Paquin, a cabinetmaker who became blind following a degenerative illness (Tirésias paintings). Two very different carpentry projects; however, both proceed from an aesthetic of disappearance and of blindness.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

Although the Lyon exhibition (Tant que les heures passent, Part I) already included a work of eroded carpentry (Macula), it really is at LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE that the artist initiated his research on falsely charred ruins, which would generate the series Sans titres (verticales) and sculpture pieces such as Laisse le vent du soir decider.

Je tuerai la pianiste thus was a structure both authoritarian and delicate that ran right across the space of LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE. A real architectural fiction on the scale of the exhibition place, the work proposed the enactment of a damaged wall partition sketched out with about sixty lengths of wood.

Note that this aesthetic of the accident, of crash was already present in Lyon in the installation Corps flottant – the name of these more or less dark and defined filaments that, fluttering next to the vitreous body of the eye, intervene between the subject and the visible world. As if working against himself, the artist has attempted to crumple the geometric schema governing some of his compositions in kit form such as Rosanna, Rosanna, Arcélor tubuline or even Urbicande, showing at the moment at BF15 in Lyon and in Morlaix Bay in Brittany. Corps flottant was an assemblage of painted aluminum tubes, curving in the air. The initial structure, formally close to those that form the rails for plasterboard on construction sites, seems to have been roughly handled, thrown into the architecture of the place so that it has become embedded in one of the corners. Although showing signs of violence, it nevertheless displays no other apparent mark of distortion. It was exhibited as new, absolutely impeccable contrary to Je tuerai la pianiste, which appears much more damaged. Carbonized, like the victim of a poetic fire, the work is exhibited broken, eroded and blackened.

Each of the verticals forming this latter work, in fact, has been carefully sanded down until the knots of wood protrude, and then are painted black. Between difference and repetition, the artist thus lets the material dictate the final form of the pieces of wood. Fluctuating, wavering, Je tuerai la pianiste was a representation, a pure simulacrum made of sculpted and painted wood. Melancholic, it evoked an apocalyptic narrative, having an aesthetic of ruins.

A broken skeletal work, Je tuerai la pianiste proposes a mentally ambiguous scenario: the end of a story in which the cause has been eliminated. We, the visitors, arrive after the accident to note the damage and the weakened ensemble without knowing why this has happened. We have been placed in front of a residue, the ruins of a world without any explanation. However, this burned carcass could appear painfully familiar. Kind of in the manner of a memorial or a monument, Je tuerai la pianiste evokes our collective memory. This is only the fragment of a vaster and more universal story, a “dynamic” fragment in sum embellished with images of all the other catastrophes, all the other devastated areas and all the other stories.

And what if the fragmented nature of this narrative in the end is only an expression of the present, a response to reality, a document-evidence forming a part of this society of spectacle, an indexed structure specific to our era?

This dark and melancholic vision of a dislocated modern world is in fact increasingly evoked in John Cornu’s work along side defence apparatus and other paranoiac device. Examples are his productions such as Par la meurtrière, Fleurs (flash-ball fired on wired glass) or even Assis sur l’obstacle presented last February at Palais de Tokyo. Inspired by the expression “Sitting on the Fence,” this latter work lies between “documentary sculpture”––if one considers that they are Czech hedgehogs or anti-tank obstacles like those that were positioned on the beaches of Normandy––, inverted Holy Crosses and certain artworks of the 1960s-1970s. Indecisive and ambiguous3, this installation brilliantly synthesizes a radical and serial aesthetic, and a more anguished “expressionist” narrative. A strange mixing that was found as well in the artist’s second Quebec production that combined conceptual work and a minimal facture in a highly poetic project.

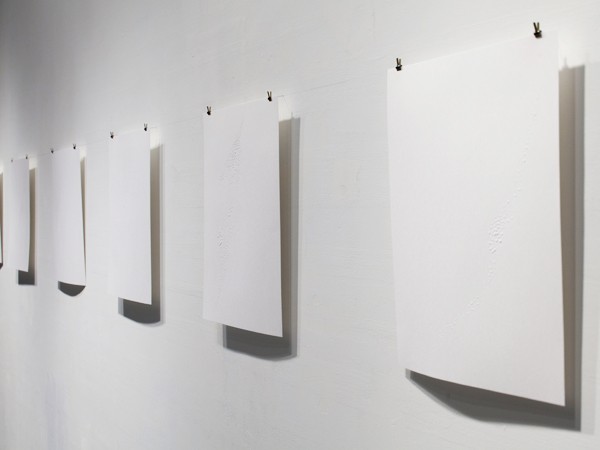

Unlike that of Je tuerai la pianist, the production of the Tirésias paintings4 was delegated entirely to a craftsperson. Well before he came to Quebec, John Cornu, in fact, had planned to entrust the making of a symbolic object to a person who has no visual referent. And it was by a fortunate combination of circumstances that the artist, while surfing the Internet in July 2009, discovered a human-interest report on Pierre Paquin5, a non-seeing cabinetmaker at work. This cabinetmaker was able to learn how to adapt his skills before he went completely blind so that he could continue to carry on his professional activities from memory. Having exchanged several emails with the cabinetmaker and presented his drawings, John Cornu asked Paquin to fabricate four stretchers, normally used to present paintings. “I have thought about this and I would like you to make painting stretchers (the wood structure that holds the canvas). I think four stretchers of 100 cm by 81 cm. The idea is to make them as close as possible to the stretchers sold in the stores. […] The best thing would be to buy a standard model (I will pay the expenses) and try to reproduce it with your skills.”6 Presented on the ground or hung on the wall, the four frames of plain wood were then displayed, exhibited for what they are, without their customary canvas.

crédit photo: Ivan Binet

In response to this and to recount this poetic human adventure, the Tirésias paintings in the Brussels exhibition (Tant que les heures passent, Part III) were accompanied by a short publication, relating the correspondence exchanged between the artist and the cabinetmaker, which furthermore, seems to be continuing…

As for the large barricade, this has been vandalized for the last time. Demolished and plundered, only about fifteen lengths of wood remained. And these were placed at regular intervals, as if to form a single work (Sans titre (verticals)), against one wall of Galerie Sébastien Ricou.

- Ardenne, Paul, Daria de Beauvais, John Cornu and Christian Alandete, «Principe d’incertitude/Uncertainty Principle». 2011, in John Cornu, Arles: Analogues editions, p. 83.

- John Cornu holds a PhD in Arts et sciences de l’art from Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne. His doctoral thesis being “Art contextual et création.”

- According to the artist, “One is in what Wittgenstein described as ‘seeing in this way’ that is to say, the fact that a same signifier is potentially the object of a plurality of signifieds.” in Ardenne, Paul, Daria de Beauvais, John Cornu and Christian Alandete, «Principe d’incertitude/Uncertainty Principle». 2011, in John Cornu, Arles: Analogues editions, p. 84.

- The title of the work is taken from the hero of Greek mythology, who on loosing his sight obtained the gift of divination, this being the capacity of “seeing” beyond the visible.

- Pierre Paquin’s Website [online]: www.ebenisterieleschutes.com (consulted on November 2, 2011).

- From emails exchanged between the artist and the cabinetmaker.

Emma-Charlotte Gobry-Laurencin